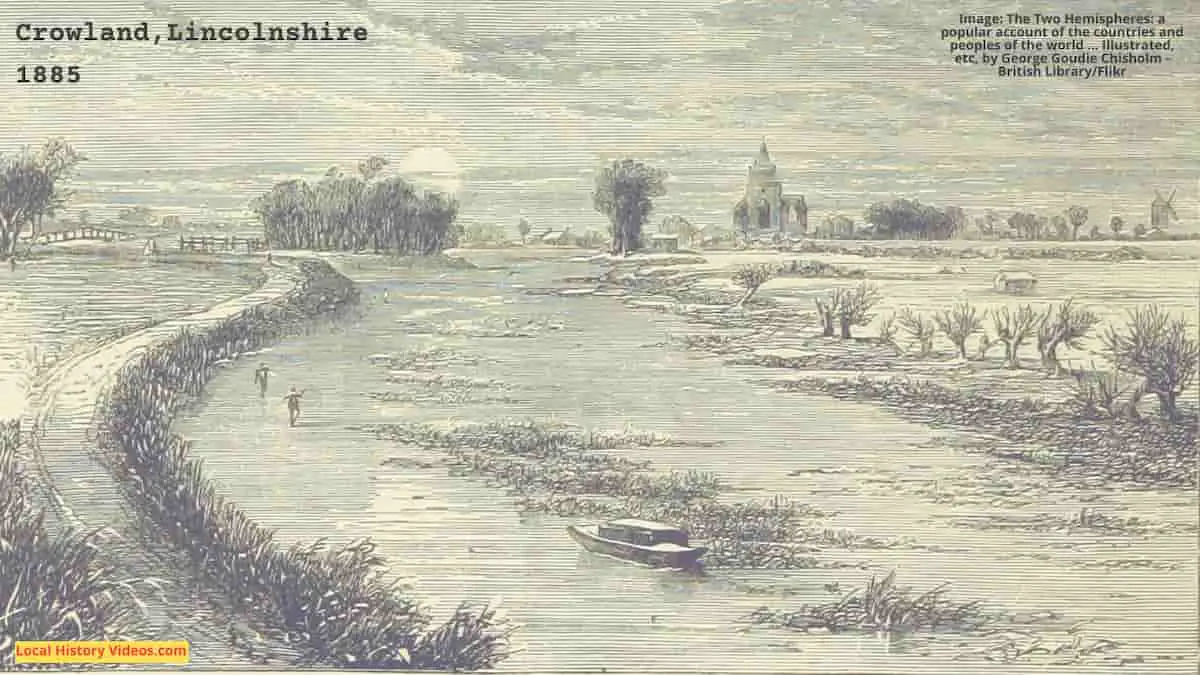

Glimpse history through old images of Crowland, Lincolnshire, England.

Crowland (1934)

Croyland Abbey was a monastic community founded in the 8th century, which became a Benedictine Order in the 11th century. The monks had been attracted to the site because Guthlac the monk lived there as a hermit between 699 and 714, when the area was an island in the Fens.

Croyland Abbey was dissolved in 1539, following pressure from Thomas Cromwell and other officials implementing Henry VIII’s The Suppression of Religious Houses Act 1535. Cromwell was executed the following year during Henry’s brief marriage to Anne of Cleeves.

The Abbey’s buildings were variously promptly demolished, badly damaged in 1643 when the Parliamentarians attacked the Royalists garrisoned there during the English Civil War, or fell into disrepair.

At some point, Croyland became Crowland for both the abbey and nearby settlement.

However, the nave and aisles were reorganised as a parish church following dissolution, and these continue in use today.

In 1934, a few seconds at the start of a newsreel showed the main street through town, the abbey ruins, and the entrance to the parish church.

Then the newsreel moves on to other places around the world, including the new traffic lights system used in an Italian city, and a nomadic family in the grasslands of the Atlas Mountains of Morrocco.

Would You Believe It? No. 5 (1934)- British Pathé on YouTube

Farmer Atkinson (1951)

A quirky newsreel from 1951 shows one of Crowland’s small farms.

Farmer Atkinson invented a simple plastic device to prevent chickens attacking members of the flock with their beaks.

Hen Spectacles (1951) – British Pathé on YouTube

A bit of Crowland history

Extract from: “The Visitor’s Guide To, and History of Crowland Abbey; Compiled from Gough and Other Authors: with an Appendix, Containing Essex’s Observations on the Origin & Use of the Triangular Bridge, &c“, by James Essex

Published in 1839

Pages 87 – 92

THE TRIANGULAR BRIDGE of Crowland is a curiosity worthy notice for the singularity of its form, more than its size. The plan of it is formed by three squares, and an equilateral triangle about which they are placed. It has three fronts; three ways over it; and three under it. It has three abutments at equal distances, from which rise three half arches, each arch composed of three ribs which meet in the centre, at top; so that whichever way it is viewed a pointed arch is seen in front, and the ribs of the opposite side behind it.

The arches spring nearly from the bottom of the abutments, which are each ten feet wide, and seven teen and a half feet distant; and the arch is twelve and a half feet high.

About the year 1752, a bridge of this kind was built in France, on the road between St. Omers and Calais. It is a magnificent dome, pierced with four large arches upon a circular plan, and supported by four abutments. Four fine canals meet under it, and as many roads cross each other on the top of it. It is called Pont sans pareil with great propriety, being excellently well contrived to answer all the purposes of travelling by land or water: the design is plain, but not inelegant; and it is an admirable piece of masonry.

The properties of the above – named bridge are wanting in that of Crowland, where the ascents and descents are so steep that neither carriages nor horses can pass over it, and persons on foot use it with difficulty: in fact it appears to have been built rather to be admired for the singularity of its form than for its utility.

It has been supposed by some that it was erected, under the direction of the abbots, to furnish a pretence for granting indulgences and collecting money; while others cannot agree with this conjecture, although it was built in an age when much artifice was practised to impose upon the ignorant for the purpose of obtaining money, because there is nothing so wonderful in its construction as to excite devotional feelings; unless the plan of it was intended as an emblem of the Trinity, there being three arches united in one arch, and three ways in one over it. Essex believes the builder had no such intention; while Gough, who is of the contrary opinion, says ” It is not improbable that this bridge was built as an emblem or representation of the Trinity; for though it has three arches, yet is properly but one groined arch; and it may, with equal propriety, be termed a bridge of one or three arches.”

That this bridge was built for a religious boundary is the most reasonable conjecture; though, strictly speaking, it cannot be a boundary, it being near five miles from the nearest part of their bounds; but it may be considered as the place from whence their bounds were measured.

On this spot a bridge has stood from the earliest period, as appears from the charter of Ethelbald who founded the abbey, and who used it for that purpose when he first settled their bounds: it was used for the same end in succeeding times, as stated in the charters of Witlaf, Bertulph, and Edred.

From this it is erroneously supposed that the present bridge was built in Ethelbald’s reign; and this opinion is strengthened by his statue being placed upon it. In the charter of Edred, dated 943, mention is made of the triangular bridge, at Crowland; but in all the preceding charters, it is the bridge, without the appellation triangular; from which it may be concluded that the first triangular bridge was not erected long before the charter of Edred was granted: but the present one is not older than the time of Edward I.; and is supposed to have been built by abbot Richard de Croyland I. who resigned his abbacy in 1303, and who first introduced the pointed architecture at Crowland: the west front excepted.

The triangular bridge noticed in Edred’s charter was most probably erected by abbot Turketyl when he restored the abbey and boundary stones, after the Danish invasion; but if it had been built with stone, it would have been guarded by a strong gate, portcullisses, and other works agreeable to the customs of the times; but as there has never been any traces of such works discovered, it is reasonable to conclude that that bridge was made of wood, and that the branch leading to the monastery was guarded by a draw – bridge; or so constructed that it might be entirely removed upon any emergency.

The present triangular bridge is of stone, and cannot, according to the style of the architecture, which was introduced here at the period before stated, be older than the beginning of the reign of Edward I.; when the causes which before prevented their building a stone bridge, after this time, no longer existed. They had now nothing to fear from the incursion of foreigners; the oppressive feudal lords were no longer so formidable as they had been, and a bridge might at that time be built without danger to the monks, who were sufficiently safe within the walls of the abbey. But why they should build a bridge which no carriage or horse could pass over, nor any foot passengers conveniently walk over, is somewhat difficult to account for. Had they intended it for common uses, without doubt those who built it would have built one convenient for every purpose; but it is the opinion of Essex that it was not intended for such uses, but for the support of a triangular stone cross, on a pedestal of the same form, set up at that time to answer two purposes; -to mark the spot from which, in all their charters, was the place from whence their bounds were measured; and for a market – cross. That it was used for the first of these purposes is very probable; and that the statue of Ethelbald was set upon the pedestal at the foot of the pyramid or cross, to commemorate their founder and benefactor, who first settled their bounds, and made that spot the centre of them.

It was no uncommon thing at the period when this bridge was erected to set crosses upon bridges, in recesses over the piers, either to mark the division of counties, or the bounds of parishes, and sometimes for religious uses, as those were which stood on the sides of public roads. For this purpose chapels were sometimes built upon large bridges, and by the side of great roads.

As no people were more tenacious of their privileges and property than the monks, without doubt they made the perambulation of their bounds as often as the state of the country permitted. These perambulations were made with solemn processions from the church to the high cross, where the host was exposed with much solemnity to the people, who there received the benediction; and, joining the procession from thence, with banners displayed, chanting litanies and psalms accompanied with music, they marched to the places where their bounds were marked by stones or crosses: and if any of them had been thrown down by storms or floods, or any broken or lost, they were set up again with the usual ceremonies. For this, and other purposes of the same nature, no bridge was better situated or contrived than this.

It served likewise for a market – cross. A market and a fair * were granted to the town of Crowland, by Henry III., the reign preceding that in which the bridge was built. Market – crosses were generally raised on high steps, the lower ones serving for those who served the market with the produce of the neighbourhood; but the space about this cross would not admit such steps, had the situation required them; therefore they made stone seats against the walls of the wings to answer the same end.

After the dissolution of the abbey, the bridge could not be used for any religious purpose; and the cross, being no longer esteemed, was most probably removed to make a clear passage over it, and the statue of Ethelbald placed on one side, which still remains, much defaced.

In these and other respects this unique piece of workmanship, one of the greatest curiosities of its kind which this country, if not Europe, can produce, has been considerably altered, but without very materially destroying its original form, which may yet be distinctly seen; and which it is hoped will long continue, with the splendid ruins of the far – famed abbey, to be the boast of the improving town of Crowland, and the admiration of the antiquarian and the traveller.

*Henry III., by charter, 1226, prohibits all men coming to the feast of the fairs of St. Bartholomew, at Crowland, from making hearses, stalls, or fixing poles, without having first obtaining license of the abbot and convent: this fair, which is now held on the 4th and 5th of September, was, when first established, held six days before, and as many after St. Bartholomew’s day. The market was granted to be holden on the Wednesday weekly, subject to tolls, to be paid to the abbot: this market is now held on the Thursday, toll free.

You may also like to see the pages about nearby Spalding or Peterborough.

More about Crowland

- Old Images of Lincolnshire, England

- Old Images of Louth, Lincolnshire

- Old Images of Immingham, Lincolnshire

- Old Images of Grantham, Lincolnshire

- Old Images of Gainsborough, Lincolnshire

- Old Images of Crowland, Lincolnshire

- Old Images of Boston, Lincolnshire

- Old Images of Scunthorpe, Lincolnshire

- Old Images of Harlaxton Manor, Lincolnshire

- Old Images of Spalding, Lincolnshire

- Old Images of Skegness, Lincolnshire

- Old Images of Scampton, Lincolnshire

- Old images of Cranwell, Lincolnshire

- Old Images of Sleaford, Lincolnshire

- Old Images of Horncastle, Lincolnshire

- Old Images of Stamford, Lincolnshire

- Old images of Keadby Bridge, Lincolnshire

- Old Images of Mablethorpe, Lincolnshire

- History in Old Images of Lincoln, UK

- Old Images of Ruskington, Lincolnshire