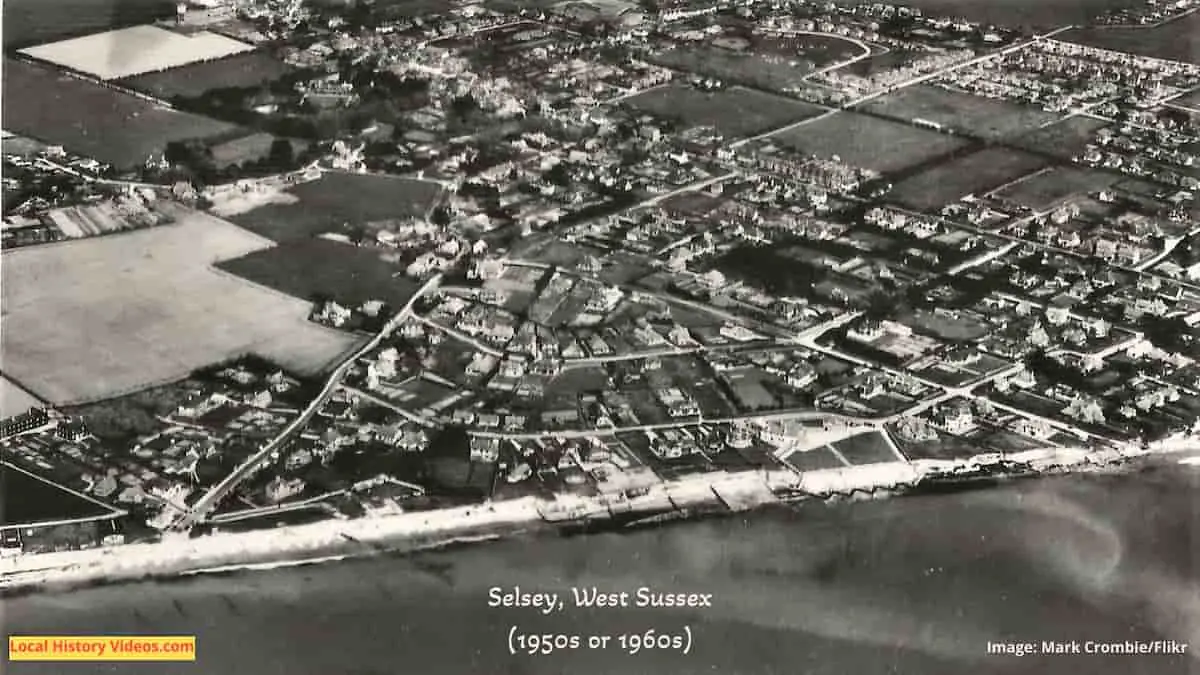

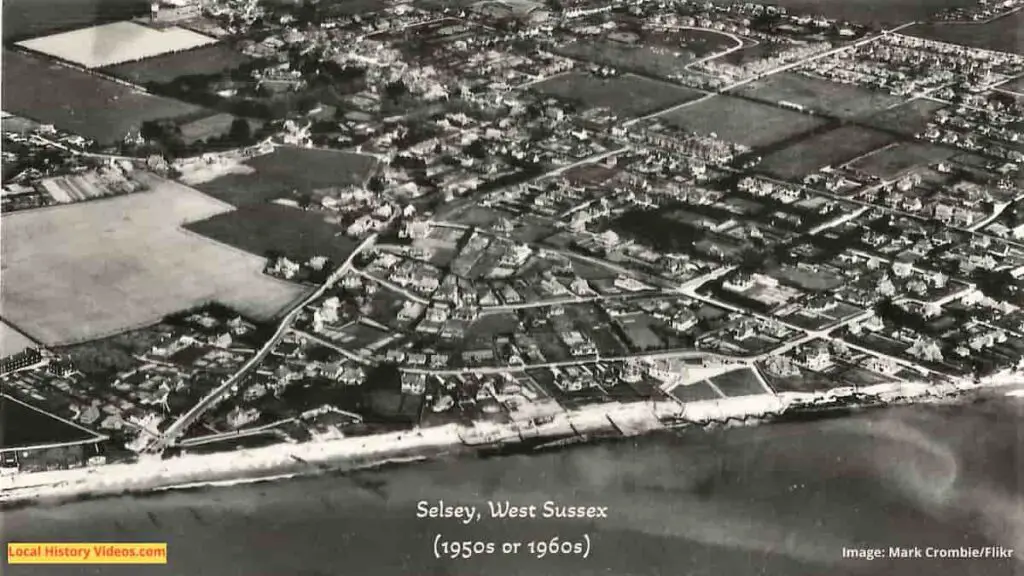

Glimpse history through old images of Selsey, West Sussex, England.

In the 1950s, the sea was encroaching on at least 20 feet of land each year, and a sea wall was required to stop this continuing.

Residents at the seafront were being asked to pay for the new sea wall, which they could pay over 30 years.

The local authority agreed that the costs should be borne by the state, was it wasn’t the law, and therefore they had to ask the residents to pay.

Two widowed sisters, Mrs Janet Parsons and Mrs Ella Poynter, lived together in a seafront bungalow. Mrs Parsons bought the property in 1948 for £2,850, and now ten years later being asked to pay the council £2,500 to build the sea wall.

Widows Say Can’t Pay (1959) – British Pathé on YouTube

Donkey Sanctuary 1964

Donkeys were still a common site on British beaches in 1964, when 60 year-old retired coal merchant John Lockwood was filmed at the home he had created for the older, sick and unwanted animals.

In addition to the 50 donkeys, he also had 10 horses and 5 dogs.

It cost £1200 a year to care for these animals, which doesn’t sound much now but at the time would have bought a small home.

Old Mokes At Home (1964) – British Pathé on YouTube

A Bit of Selsey History

Extract from: Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Review, Volume 281

Published in 1896

Pages 197 – 199

The intelligent youth of this country, trained under the national system of elementary education, are credited by a vulgar error with a knowledge of everything. As a consequence of this, it is generally found that they know nothing, and when, as often happens, those who are considered the most forward in the geography of their native land are questioned regarding the position of Selsey and the meaning of the word, they stand abashed and dumb.

It would be going too far to suppose that the majority of adults would fare any better on being similarly tackled, and they will pardon us when we remind them of the fact that Selsey constitutes the south-westerly projection of Sussex, that the small village which does duty as its capital signifies, according to the Venerable Bede, “the Isle of Seals,” and that the spot where the island terminates is called Selsey Bill, possibly from its supposed resemblance to a bill-hook.

Can it be true, we hear some say, that seals once made this wave-beat shore their home? Even so. Once upon a time, which is only another way of saying nobody knows when, seals thereabouts gambolled the live-long day, and were as plentiful as blackberries are in the hedges nowadays.

The public taste throughout Sussex, if we may believe the monastic chroniclers at this remote period of its history, sorely needed what Mrs. Jarley, of waxwork celebrity, called “improving,” or, as we should say, evangelizing, and it will occasion no surprise to any to learn that the desolate spot was soon graced by a monastery.

Selsey today is an uninviting tract enough, but what it must have been in Anglo-Saxon days we can only faintly imagine. The splash of the seal and the cry of the seagull alone woke the slumbering echoes.

To make a long story short, Wilfrith got a grant from his patron of Selsey, which then contained eighty-seven families and two hundred slaves of both sexes, whose manumission he procured, to his honour be it said, by submitting them to the ordinance of baptism.

Wilfrith, of course, converted Selsey into a bishopric and erected his waliopa, or stool, in a church which was reared in honor of Saint Peter, most probably in remembrance of his more splendid church in York.

It appears that he soon won the affections of the islanders, who must have been either very simple or very stupid, if not a combination of both.

Once it is recorded that there was a drought upon the land which lasted three years. During this long time, the wretched inhabitants were accustomed to assemble in gangs of fifties and to throw themselves into the sea to perish, in absolute ignorance of that “gentle craft” which Isaac Walton and Charles Cotton did so much to popularize. Wilfrith, we learn, was instrumental in stopping this wholesale suicide only by procuring a number of fishing nets and teaching the benighted islanders the use of them.

A combination of political circumstances effected the recall of Wilfrith to the metropolitical see of York in the year 685. For nearly fifteen years afterwards, the see of Selsey remained vacant, but on the division of the South Saxon Kingdom by Ine, Cardwalla’s successor, it was revived, and more than twenty prelates filled it between that date and the Norman Conquest. Among the number was one Sigga, who was present at the council of Cloveshoo, convened under Archbishop Cuthberth for the restoration of ecclesiastical discipline.

But Selsey was destined to share the fate of Dunwich and other lost towns. Of the monastic buildings which were tenanted by Wilfrith and his clergy, and their successors, only a few now meet the eye of the searcher for them. The fishing boats glide smoothly over what was once the “Bishop’s Park” and the “Bishop’s Coppice.” The little town which grew up around the monastery vanished under successive encroachments of the sea, and the tides ebb and flow over its site.

William Camden, the celebrated antiquary, who wrote his “Britannia” in the days of Bluff King Hal, tells us that at that time the ruins of Selsey’s monastery were plainly discernible to the naked eye beneath the waves. At that date, too, the episcopal park, well stocked with deer, was not submerged, and the fact of its existence is still perpetuated on a line of anchorage along the south-eastern coast of Sussex, which is locally called “the Park.”

Dr. Stephens prints a copy of a curious mandate, which was issued in 1407 by Bishop William Rede, whose wrath had been kindled by the depredations of divers poachers in Selsey Park. The mandate sets forth that it had come to his lordship’s ears, “through trustworthy sources, that certain sons of damnation,” whose names and persons are unknown, “seduced by a devilish spirit and abandoning the fear of God, hunted in our park at Selsey with hounds, nets, arrows, and other instruments on the night of Jan. 31; broke down the fences of the park, and dared to chase, slay, and carry away deer and other wild animals.”

The missive, indited at Amberley Castle, where Bishop Rede was then residing, concluded with threats of the greater excommunication upon the offenders with “cross upraised, bells ringing, and candles lighted” in every church in the deanery! It is to be hoped that these offending “sons of damnation” were not among the vicars and rectors in the deanery of Boxgrave, to whom this epistle — a very different one, it must be confessed, from those of St. Paul and St. John – was addressed; and that, if they were, that they escaped. Otherwise this successor of the Apostles, who was evidently not one who suffered fools gladly, might have added to his threatenings by making his crozier acquainted with their skulls at his next visitation. In those days a terrible faculty of wrath often resided in ecclesiastical dignitaries, and their crooks were sometimes put to uses during their peregrinations among their wayward flocks which are now associated only with the policeman’s truncheon.

We may mention that, after languishing in obscurity for many hundreds of years, the little village of Selsey crept once more into local celebrity by reason of an inventive manufactory of mousetraps, which was established in its midst by the enterprise of one Mr. Colin Pillinger.

One of the results of the Council of London which was convened at St. Paul’s in 1075 was the transference of the see of Selsey to the city of Chichester, some nine miles distant. Stigand, who was the last bishop of Selsey, was also the first bishop of Chichester. England now owned Norman sway. It might be a matter for surprise that Chichester should have been selected for the new see, but there were good reasons why it was. For one thing, the city was well fortified; for another, it lay within easy distance of Bosham and its harbour, which was a very convenient place of departure in those days for the coast of Normandy. Those who have ever studied minutely the series of incidents depicted on “The Bayeux Tapestry,” either in the originals at Caen or in copies of them, will remember the particular one which depicts the embarkation of Harold, and his return for the Norman shores, at Bosham; the ancient church, which still stands, being depicted in the background. Great, indeed, is the difference between the Bosham of those days and the Bosham of these.

More about West Sussex

- Old Images of West Sussex, England

- Old Images of Worthing, West Sussex

- Old Images of Steyning, West Sussex

- Old Images of Selsey, West Sussex

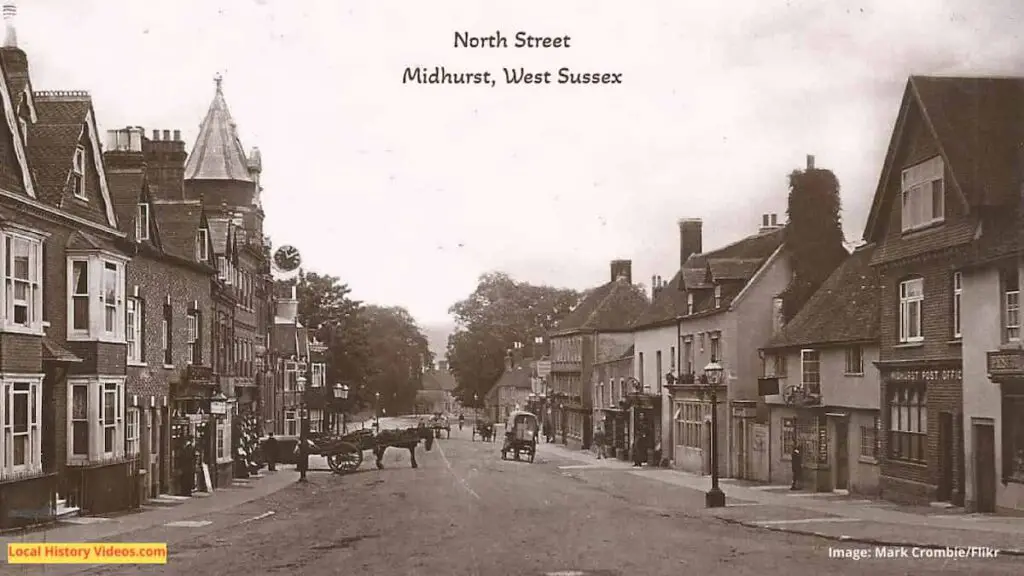

- Old Images of Midhurst, West Sussex

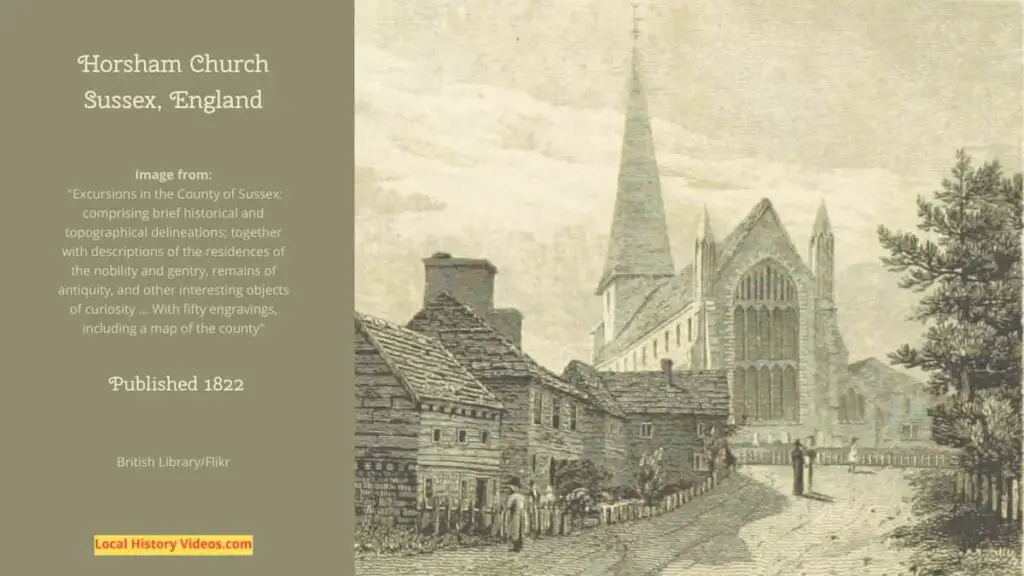

- Old Images of Horsham, West Sussex

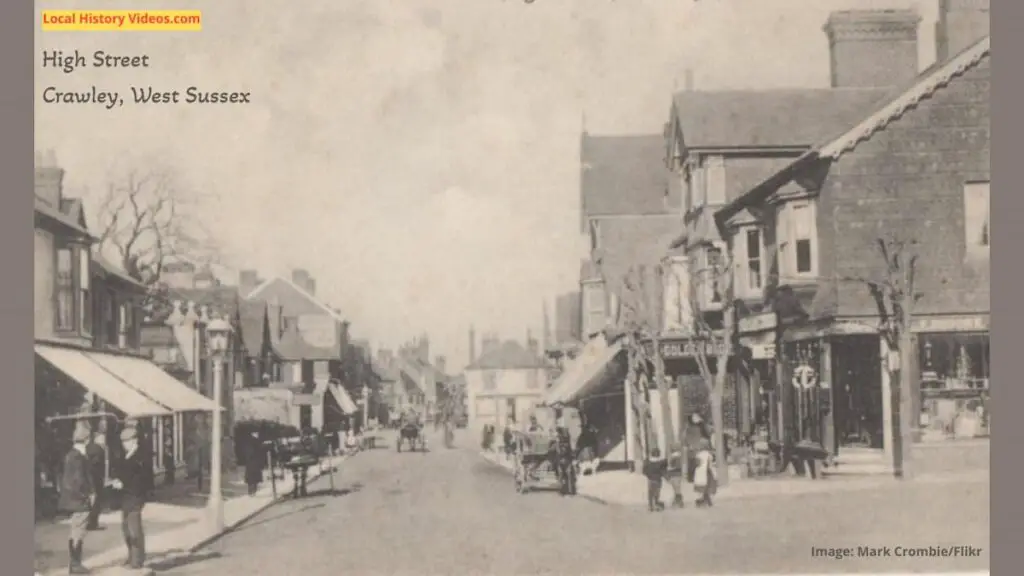

- Old Images of Crawley, West Sussex

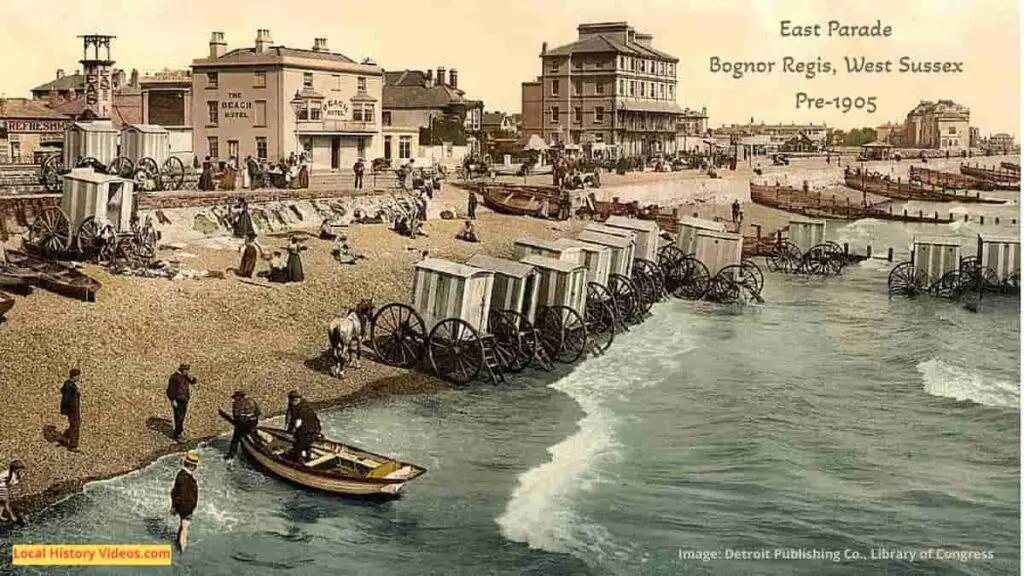

- Old Images of Bognor Regis, West Sussex

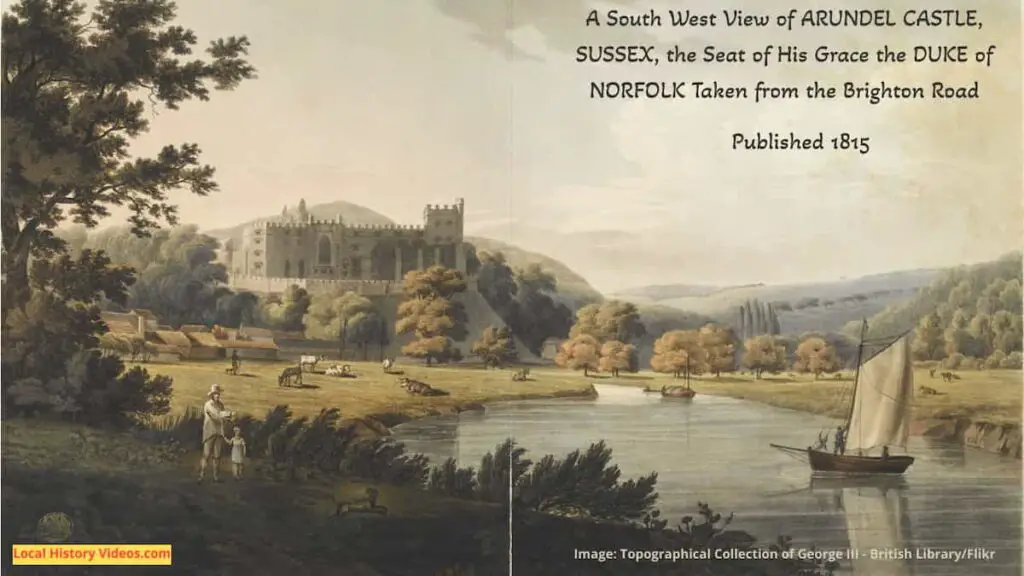

- Old Images of Arundel, West Sussex

- Old Images of Haywards Heath, West Sussex