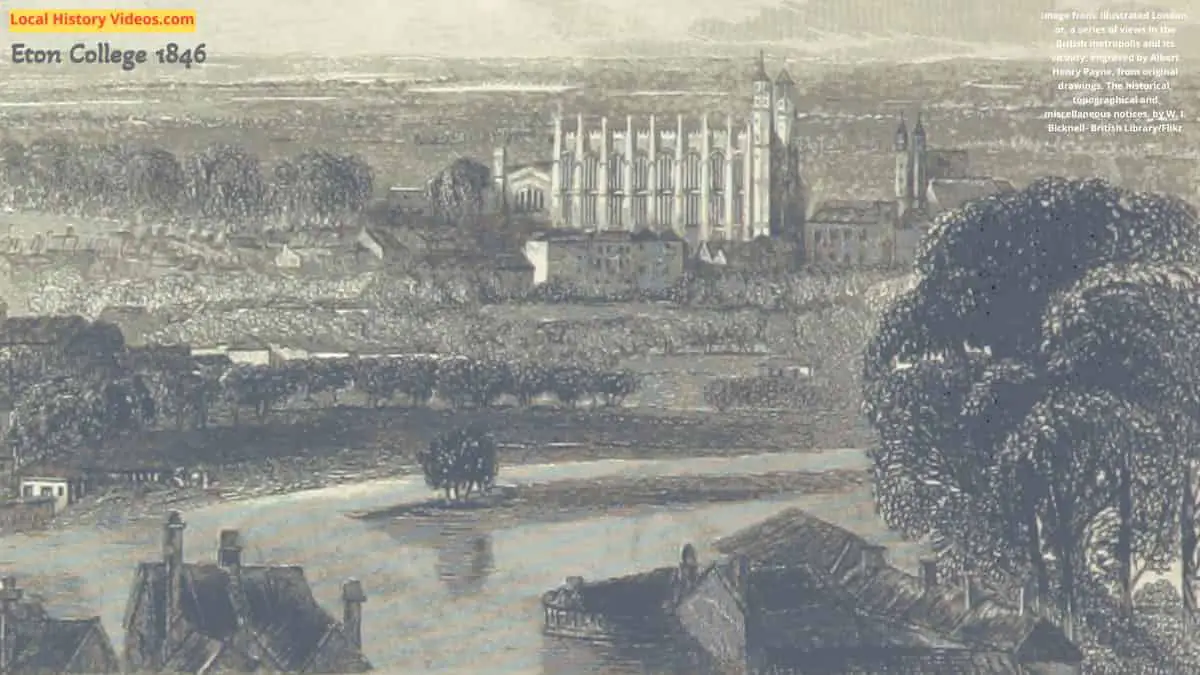

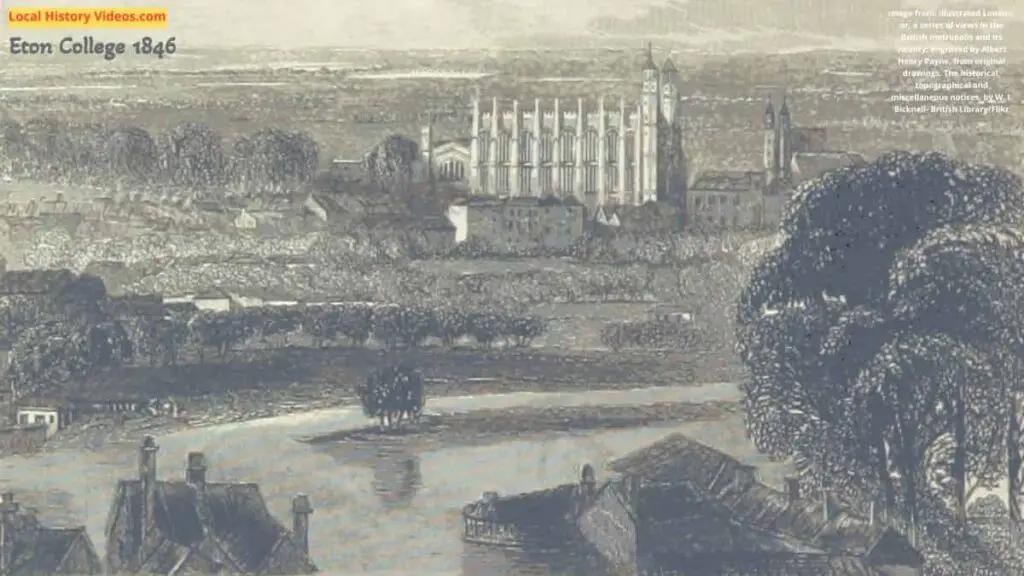

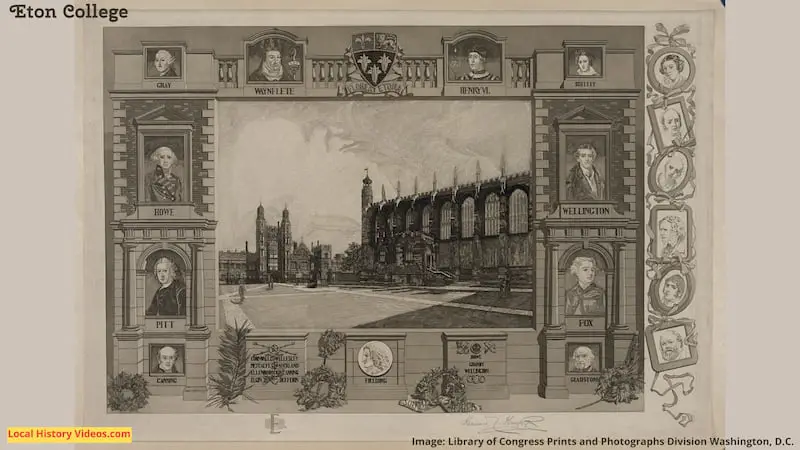

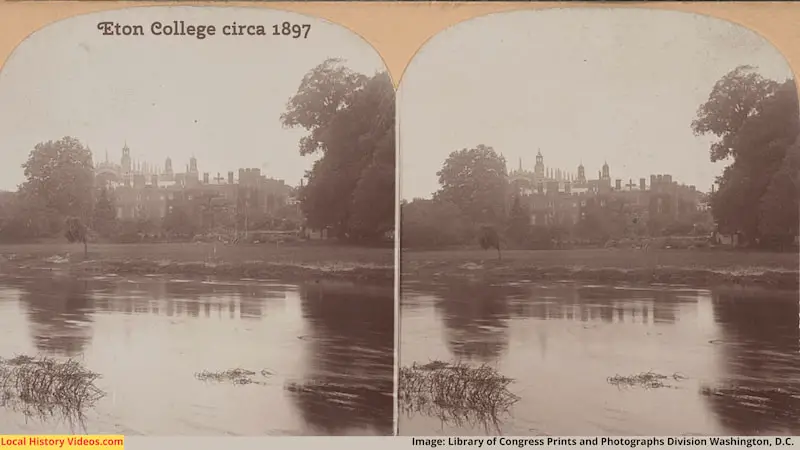

Glimpse history through old images of Eton College, Berkshire, England.

Old Pictures of Eton

Old Photo of Eton College

WWI Officer Training Corps

The college’s War Memorial walls list a large number of former students who died in the Great War, later known as World War I. Perhaps some of them were present during this event for the OTC, before leaving for the conflict.

Eton College Otc (1914-1918) – British Pathé on YouTube

1925

Schoolboy Sportsmen (1925) – British Pathé on YouTube

4th June, 1926

The Glorious Fourth Of June (1926) – British Pathé on YouTube

Beagles 1927

Eaton College Beagles (1927) – British Pathé on YouTube

Race 1928

ENGLAND: Half mile race final at Eton (1928) – British Pathé on YouTube

Steeplechase 1928

Eton College Steeplechases (1928) – British Pathé on YouTube

Royalty 1930

New Colours For Eton Otc (1930) – British Pathé on YouTube

Wall Game 1930

Eton Wall Game (1930) – British Pathé on YouTube

Wall Game 1930

Eton Wall Game (1933) – British Pathé on YouTube

Head’s Retirement 1933

The Retirement Of Eton’s Head Master (1933) – British Pathé on YouTube

Wall Game 1934

Eton Wall Game (1934) – British Pathé on YouTube

1934

Big Splash At Eton (1934) – British Pathé on YouTube

1935

Windsor And Eton (1935) – British Pathé on YouTube

More 1935

Scenes Of Windsor And Eton (1935) – British Pathé on YouTube

Race 1935

Over Or In (1935) – British Pathé on YouTube

Wall Game 1937

Eton Wall Game (1937) – British Pathé on YouTube

4th June, 1938

Fourth Of June At Eton (1938) – British Pathé on YouTube

Wall Game 1938

QUIRKY / SPORT: Eton Wall Game (1938) – British Pathé on YouTube

Steeplechase 1938

Eton College Steeplechase (1938) – British Pathé on YouTube

4th June, 1950

Fourth of June celebration at Eton (1950) – British Pathé on YouTube

Field Game 1959

Eton Field Game (1959) – British Pathé on YouTube

A bit of Eton College’s history

Extract from:

A History of Eton College, 1440-1875

by Sir H. C. Maxwell Lyte

Published in 1875

Pages 129 – 131

Sir Thomas Smith recovered his liberty after a short imprisonment, but only on disgorging a large sum of public money which he had embezzled. At Eton, he was treated with great deference. His predecessors and successors have been styled “Master Provost” or “Mr. Provost,” but the Fellows generally styled him simply “our Master.”

Several members of the College were not slow to follow the example of Sir Thomas Smith in taking to themselves wives, though it is difficult to see how they could justify so distinct a breach of the Statutes.

The dismissal of several Chaplains, who were no longer required for the celebration of solitary masses, may have provided rooms for the reception of women and children, the very thought of whom would have scandalized the pious Founder.

Barker, the Master, received a royal license in 1551, enabling him to retain his post, though he was avowedly married; but such proceedings were regarded with aversion by the severer portion of the community.

A married priest was considered capable of almost any enormity, and Barker had already come in for his share of abuse.

William Goldwyn wrote to Sir Thomas Smith on the 5th of May, 1549, to explain:

“Whereas ill reportt hathe byn that the scholmaster shuld be a Disepleyare Cardeare Riatore or Gameare nott applyeng his schole trewlye, that Reportt is manifestlye false, know he is none of that sortt. I can fynd no faught in hym butt (as I have honestly informed hym) he is sumwhat to gentle and gyvethe his scholears more licence, thane they have byn usid too before tyme, of the wiche thing evill tounges mey spred mutche matter and diffame witheoute care of ony good redresse. I trust ther be no suche in our companye.”

One of Barker’s pupils met with an untimely fate, which led to one of the few inquests that have ever been held within the Liberty of the College.

From the account of the proceedings on that occasion, it appears that one of the scholars named Robert Sacheverell was in the “pleyeng lease” about seven in the evening on the 29th of July, 1549, and there went to bathe at “le watring-place” with some of his companions.

While in the water, he was carried away by the stream to a place known as “le whirlpole,” and so disappeared.

The jurors, therefore, pronounced “that water execrable, and the cause of his death; on whose soul may God have mercy.”

This last sentence has a Catholic sound, but, in point of fact, the College authorities had followed the successive changes in matters of religion.

Sir Thomas Smith had been a supporter of the Reformation from his earliest years, and several of the Fellows shared his views.

The changes under Henry VIII had been chiefly political, but those under Edward VI extended to the services of the Church.

About a month after the election of Smith, the images at the high altar were pulled down and carted away; and the College lost no time in purchasing a book of the Homilies and a copy of the new Communion-book.

In 1551, the embroidered frontals of the other altars were sold, the Provost and such of the Fellows as wanted any, buying them for their own purposes.