Glimpse history through old images of Ascot Racecourse, Berkshire, England.

Improvements 1934

An “All Weather” Ascot (1934) – British Pathé on YouTube

Royals 1934

Mayfair Migrates (1934) – British Pathé on YouTube

Runners 1938

Cross Country Race On Ascot Course Lner (1938) – British Pathé on YouTube

Horse Races 1951

Ascot festival horse races (1951) – British Pathé on YouTube

1952

Wonder Horse (1952) – British Pathé on YouTube

1958

The Gold Cup (1958) – British Pathé on YouTube

1962

Royal Ascot (1962) – British Pathé on YouTube

A bit of Royal Ascot History

Extract from:

All the Year Round, A Weekly Journal · Volume 18

Published in 1877

Pages 377 – 381

ROYAL ASCOT.

AWAY in the far north – in the Macbeth country, the country which brooks not that its magnates should run horses, even in France, on Sundays – there is a famous boulder-stone. Not the sculptured stone of Sweyn, nor the stone whereon witches were burnt, in the good old merry times; but a stone quite as significant as these – the tombstone, as it were, of which civil war in England – beneath rested quietly enough the relics of the Jacobites, till the very name of that faction became confused with those very different folk, the Jacobins; and finally vanished from human ken altogether. This boulder stone is huge of size – a notable landmark on Drummossie Moor, now much cultivated and enclosed, having become changed, even as the field of Waterloo has become changed. Where grew, a century ago, heather and bracken, are now smiling cornfields. Hardly yet does corn grow up to the edge of the great stone of unsavory renown in countries beyond Tweed.

This is Cumberland’s Boulder stone; the rock on which William Augustus — sometime Duke of Cumberland and Generalissimo of the Forces – ate his breakfast, on the morning of the 16th of April, 1746. Here also, later in the day; the duel between tartan and scarlet, claymore and cannon, being over; the victorious duke is said – only said, be it noted – to have written, on a certain playing-card – the nine of diamonds, hence called the curse of Scotland – the order to give no quarter. The existence of this order is by no means proved, and it is more likely that the idea of giving quarter to bare-legged caterans occurred to neither general nor soldier, than that any precise order to slay and spare not was spoken – not to say written out – on a playing-card for paper and the great boulder-stone for a writing-desk.

There is nothing truculent in the aspect of so-called “Butcher” Cumberland. He never grew old enough to be savagely cruel. In the portraits of him in his youth, he appears as a large-eyed boy of cherubic aspect. As time rolled on, he accumulated adipose tissue, particularly about the jowl – after the manner of his race – and his looks became heavier and more stolid; but when he won the battle of Culloden, at the age of twenty-five, there was nothing savage in his outward appearance. The engraving before me represents a pleasant, cheerful young man, already showing signs of incipient obesity, with a three-cornered hat cocked jauntily over his eye, with rich lace cravat round his throat, his vast full-bottomed coat sweeping down to the tops of his huge jack-boots.

This martial figure, grasping the baton of command, is mounted on a piebald horse, prancing in fashion suggestive of the circus. Again, I see him in a medallion – still plump, rosy, and good-humoured. Beneath him, the artist has represented a ragged Highlander, prostrate among his own inhospitable mountains, his claymore shattered, his buckler – inaccurately shaped by the way – broken. Under this design is the legend:

“Thus to expire be still the rebel’s fate, While endless honours on brave William wait.”

He well deserved the epithet of “Brave William.”

The sword of Culloden had been fleshed at Dettingen and Fontenoy. By the side of his peppery little father, he was gloriously wounded, and despite his youth, appears to have been a better commander by far than the veterans Cope and Hawley. The former of these had been easily thrashed at Preston Pans, and the latter roughly handled at Falkirk.

Cumberland, however, took every advantage of the blunders of his wretched adversary, the young Pretender, who had not even the courage to charge at Elcho’s bidding, at the head of his troops. He never, or very rarely, interfered in politics, his ambition being purely military.

Shortly before Culloden, he had managed to escape an unpleasant match – “that bolus, the Princess of Denmark,” as Walpole ungallantly styles the lady. “The duke, you hear, is named generalissimo, with Count Koningseg, Lord Danmore, and Ligonier under him. Poor boy! he is most Brunswickly happy with his drums and trumpets. Do but think this sugar-plum was to tempt him to swallow that bolus!” At the moment Walpole wrote this, he, like the duke’s father and his ministers, was evidently blind to the capacity of the young prince. Lord Granville himself, too giddy to sound Cumberland, treated him arrogantly in the matter. Hereat the duke, accustomed by the Queen and his governor, Mr. Poyntz, to venerate the wisdom of Sir Robert Walpole – then on his death-bed – sent Mr. Poyntz, the day but one before Sir Robert expired, to consult him on how to avoid the match. Sir Robert advised his Royal Highness to stipulate for an ample settlement. The duke took the sage counsel and heard no more of his intended bride.

The victory of Culloden was greatly appreciated by the Southron, and for a while, the soldier prince was the most popular man in England.

Twenty-five thousand pounds a year were settled on him for life, besides the fifteen accruing to him at the king’s death; but the trial and execution of the rebel lords brought about a revulsion of feeling. The London inns were crowded with rebel prisoners, and people made parties of pleasure to hear their trial; the Scots, meanwhile, testifying loudly everywhere against the duke, for his severities in the Highlands. It would seem, also, that he had some influence in turning the king’s mind from mercy towards Lord Kilmarnock. Popular feeling at last exploded in the jest which has labeled him forevermore. It was proposed, in the city of London, to present him with the freedom of some company when one of the aldermen said aloud, “Then let it be of the Butchers.”

Fortune also frowned upon him in the field. Two years after Culloden, he was beaten by Marshal Saxe, near Lawfeld, and ten years later lost the battle of Hastenbeck to Marshal d’Estrécs; a not very brilliant close to the career splendidly inaugurated at Dettingen. The English ministers appear to have feared his capacity.

The ambition of Lord Hardwicke, the childish passion for power of the Duke of Newcastle, and the jealousy of Mr. Pelham combined, on the death of the Prince of Wales, to exclude the Duke of Cumberland from the Regency nominated in case of a minority. When his two political friends, Lord Holland and Lord Sandwich, deserted him, and even his father threw him over on the convention of Kloster Zeven, the unlucky prince devoted himself exclusively to landscape gardening, encouraging the manufacture of china at Chelsea, and horse racing, and left his mark on each.

Virginia Water – one of the prettiest artificial lakes in the world was constructed under his eye. He bred the celebrated racehorse Eclipse; and last, but not least, he founded Ascot Races.

In “Butcher” Cumberland’s time, and for many years after, Ascot races were far from approaching their present splendor.

Ascot, in fact, was long styled a “country meeting,” as distinguished from the solemn celebrations at the metropolis of the turf.

Even those would hardly bear comparison with a third-rate meeting of the present day. One or two races, or matches, preceded dinner and abundant port-wine or punch; then came another race or two, then cock-fighting, supper, dice, cards, and more drinking.

Still Ascot went on until the Escape affair disgusted Prince Regent Florizel with the turf, and then royal eyes looked kindly on the little “country” racecourse.

At that moment, the star of Goodwood had not yet arisen, and Ascot became the spot towards which the “best people” gravitated in leafy June.

Unlike Epsom, proudly avers the contemporary chronicler, “the scene lies too far from London for the pollution of sheer cockneyism; it is near enough for a gallant display of the rank and fashion and beauty of the metropolis.”

Beautiful in natural features, it can hardly be called. There is a sandiness, a barrenness about Ascot Heath, which, especially under certain circumstances, produces a feeling of depression, but its approaches are eminently lovely and suggestive of innumerable pleasant reminiscences of Shakespeare, Denham, and Pope – of Falstaff and the buck-basket, of Mistress Anne Page and Master Slender.

All these attractions had Ascot in the day of George the Fourth of that name, but it was said that the gay visitors cared much less for them than for that “one great interest which these present races enjoy, beyond all other public amusements whatsoever – it is at these races that the king appears amongst his people, and takes a common interest with them in their sports.”

Judging by a picture before me, and from other evidence needless to recapitulate, I doubt the extreme popularity of the first gentleman in Europe in the year of grace 1820. But whether to see the king, or the horses, or each other, people came to Ascot eagerly enough in the ante-railway days.

By six o’clock, everybody within five counties round was awake, and getting breakfast as fast as possible.

By nine, Park Street was lined with embowered wagons filled with glowing lasses, ancient and buxom dames, with fathers and husbands, brothers and sweethearts to match, and drawn by sleek, plump-haunched, flower-bedecked horses, driven by sun-burnt youths, each with a nosegay in his Sunday vest.

The whole countryside was en route for the racecourse.

Meanwhile, from Windsor and from London, came the noble army of fashion, tight-waisted, curly-brimmed, leg-of-mutton-sleeved fashion, pale from early rising and a long drive in the hot morning.

Male fashion came in vehicles, the very names of some of which have lost all significance, buggies and curricles to wit, and gigs vast of wheel and rakish of air.

Female fashion came in post-chaises and stage-coaches, in open landaus and glittering barouches.

The heath itself was alive with bustle. The alloy of rabble, “adds a contemporary writer, “is a mere nothing,” and then continues in a fine burst of metre:

The king came on the course in a carriage and four, He alighted with firmness of step from the coach, To the joy of the thousands who hailed his approach. With a dignified bow and a wave of the hand, He approached to the stairs and ascended the stand. He appeared in good health, and in short quite the thing, And the multitude shouted “Long, long live the king!” He was dressed in a plain blue surtout with a star, And looked better, ’twas noticed, than last year by far.

Hardly so beautiful, so genteel, and so intensely loyal is the narrative of a gentleman from Suffolk, also an eyewitness. “The crowd was intense, like the heat; splendid, genteel, grotesque; many in masquerade, but all in good humor – dandies of men; dandies of women; lords in white trousers and black whiskers; ladies with small faces, but very large hats; Oxford scholars with tandems and randoms; some on stage-coaches, transmogrified into drags – fifteen on the top, and six thin ones within; a two-foot horn; an ice-house, two cases of champagne, sixteen of cigars; all neckcloths, but white; all hats, but black; small talk with oaths, and broad talk with great ones, cooled with ice, and made red-hot with brandy and smoke; all four-in-handers; all trying to tool ’em; none able to drive, but all able to go with the tongue. An Oxford slap-bang loaded in London; Windsor blues freighted at Reading; Reading coaches chockfull at Dorking; a Mile-end coach-wagon; German coaches, Hanoverian cars, Petersburg sledges, and phaetons; St. James’s cabs; Bull and Mouth barouches, waggoned by Exeter coachmen.”

No place, no amusement, no holiday-making is so enchanting to the softer sex. Gentle and simple, grave and gay, all are on tiptoe of joy, and out jumps nature from both ends – eyes and foot.

Lords’ ladies tastefully costumed with roses and lilacs untainted, or rather unpainted by Bond Street; farmers’ daughters and farmers’ wives sparkling in silks, rosy in cheek, tinted by soft breezes and bottled ale.

A sacrilegious scribe this of the Georgian period, writing under the signature of Patroclus in the Sporting Magazine of fifty years agone. He evidently saw more of the crowd than the poet cited above. He was not so absorbed in the contemplation of royalty, as to ignore the glee singers and stilt-dancers, the boxers and the gypsies, the thimble-riggers and the pickpockets. He got home safely after his all-sprightly old Patroclus – finished dinner and his bottle, and wound up by “chanting” – gentlemen of a sporting turn did not sing fifty years ago, they “chanted” – that famous song, which begins by demanding a bumper of Burgundy for the singer, “for those who prefer it, champagne,” and concludes with a health to the king, God bless him!

Ascot in modern times has changed its character completely. Far from being a select meeting protected from the incursion of the million by its distance from London, it is now, outside the precinct of the royal, stewards’, and grandstands, very like any other racecourse.

Yet there is a difference, for at Ascot, as at Newmarket, there is a resident population, a select constituency bestowed in the prettily embowered cottages which line the New Mile.

The owners of many of these snug habitations elect to live the year through at Ascot – save in the race week – when they get a handsome yearly rent for five days’ occupation.

Those curious personages, noble, gentle, and otherwise, whose scheme of existence is perpetual motion from one racecourse to another, are content to pay an enormous price for their accommodation on the spot they pitch their tent upon for the time being.

There are jovial times tempered only by the in-and-out running of horses in these pretty dwellings during the Ascot week: great consumption of the good things of this life, and much talk of those other good things “of the turf not quite so easy to compass.

The season is in itself a charm, winds and cold drifting rain not unfrequently turn the Epsom celebration into a week of tribulation to lungs and pocket, but a “wet Ascot” is looked upon as a positive injury from two points of view.

First, horses, like the seventh ballet in Der Freischütz, are apt to go askew in heavy ground; secondly, the stupendous artillery of bandboxes remains undischarged; ravishing toilettes, too pretty and pronounced to appear in the park, instead of bursting into flower, lie concealed in their calices of cardboard, and the feminine heart waxes almost as sore as the masculine organ when “a screw is loose” with the favorite.

The birds are there, but their beautiful plumage, span new, and mostly unpaid for, may not be donned merely to be draggled in the mud.

It is pitiful, wondrous pitiful, for between Ascot and Goodwood fashion may change, and it is reasonably certain that whether it changes or not, the lawn under Trundle-hill in hot July will need other raiment than that proper to Ascot-heath in summer’s first youth.

If the cardboard calices open not at once, when are they to develop their hidden treasure? A source of much agony of mind to the constructive genius of New Burlington Street. It has fallen to the lot of the present writer at least twice during a misspent life, to look ruefully at royal Ascot, to button fiercely round him that garment which the admirable author of Tom and Jerry designates an “upper Benjamin,” to smoke ferociously his biggest cigars, to suffer unholy cravings for hot brandy and water, and, sorrow’s crown of sorrows, to back the second horse for every race.

A wet Ascot is good neither for men nor women, for horses nor the backers thereof, for prophets nor for newspaper columns. One type of humanity alone rejoices, and he only in chilly fashion.

The valiant bookmaker eats his sandwich, deftly constructed of a beefsteak of about a pound in weight and a couple of slices of toast, with rare relish; the frequent performance of the operation known as “skinning the lamb” having given a zest to his frugal meal.

But when the sun shines, as it did on the memorable day when Ely and General Peel ran their famous dead heat for the Gold Cup, called during a period of Russian friendship the Emperor’s Vase, our modern Ascot is fully as blithe as that described by the scribe of the Georgian era.

The hotter the day, the more enjoyable is the breeze, which is never absent from the Berkshire heath.

Since the revival of coaching, the resuscitation of the spanking tits which at one time appeared as dead as Boadicea’s chariot pair, the heath has put on some semblance of its old aspect.

Great Gainsborough hats, and cutaway coats of the genuine Regency pattern, suggest many points of resemblance with the old racecourse, but the influx of the general public is so great that the once distinctive feature of aristocratic Ascot is gone.

Yet the royal stand presents as pretty a sight as can be seen on a summer day. Every color and combination of color may be seen on the greensward – dark prune velvet; gray satin, with additions of luminous steely material, giving the wearer the air of a female crusader; ruddy hues, looking over hot at midday; bottle-greens and mysterious olive tints, awkwardly contrasting with the grass; and blazing yellows, staring back boldly at the sun himself.

Lady Haileybury is there, you may be sure, dressed in the latest fashion, carefully studying her card, and giving her pet commissioner her commands to put her on a “pony” at a certain price. A valiant dame this, in whom years have not quenched the love of excitement.

There are younger ladies too, who risk, on the sly, a “tenner,” or perhaps a trifle more if they “know something;” and others whose object in life appears to be to look as pretty and as well-dressed as possible.

Lady Rattlepole is to the fore as usual. When is that intrepid but juvenile matron not before the public eye? That little squabble with her fast-going lord and master has happily been patched up, and her ladyship sails magnificent in all the beauty that nature, and pearl powder, rouge, and an eelskin dress can confer. Not perhaps a model for imitation, but as a thing of beauty, unlikely to prove a joy forever, absolutely incomparable.

In the grandstand, far, too far removed – as the public who pay their money persistently growl – from the winning-post, is a brilliant but heterogeneous crowd. They have come to see the races and each other, and to be seen. So far as the finish of the races is concerned they might as well be at Slough.

The large spaces occupied by the royal and stewards’ stands effectually thrust back into the distance the thousands whose guineas and half-guineas really support the royal meeting. But they have compensation for this grievance in the prospect of the royal cortège, as it is called; Master of the Backhounds, yeomen prickers, and Royal Highnesses, Serenities, and Transparencies in open carriages; almost as brilliant a spectacle as that afforded by the wearer of the blue surtont and single star. Shouts of welcome are raised, royal and serene personages bow graciously, and, the thrilling moment past, there is time to look around at the dwellers in the grandstand – an epitome of England.

In the best places are those peers and pillars of the State who have not been honored with invitations to the royal stand, and side by side with them, open-handed wine merchants, wealthy ironmasters – not quite so wealthy as a year or two since – great cotton lords, also not so rich as heretofore; members of parliament, of the bench, and of the bar; fashionable artists and dentists, sculptors and surgeons; country gentlemen with an unmistakable five-to-two look in their great blue eyes, spotted cravats, and horsey continuations; and a great army of London tradesfolk, dressed in their best, with their wives and daughters with them – papa’s “goings during the Epsom week being condoned by a family visit to Ascot.

Mr. Curlington, the eminent hairdresser, is beautiful to look upon, but uneasiness betrays itself in his countenance. He has heard of a “good thing” for the great race, and is burning to “get his fiver on at the best price,” but cannot escape from the “missis and the girls” to make his modest venture. The “missis” is gorgeously attired, and quite oblivious of the fact that an eelskin dress displays her Juno-like outline just a little too distinctly. She is supremely happy and is never wearied of pointing out to her daughters, who have never been contaminated by contact with the shop, the noble clients of that profitable establishment whom she perceives among the company assembled; but she keeps an eye on Dolfy, “whom she secretly believes to lose a large fortune in betting every year.” Dolfy “knows that the eye of the ‘missis’ is on him. He feels that washy gray orb piercing through his elegant dust-coat and the smart cutaway into the recesses of the pocket, where lurks a tiny gilt-edged betting-book, and mentally wishes his amiable and – as to the younger branches – accomplished family at Jericho. The numbers go up, and still there is no hope of indulging his mania for speculation, when suddenly Captain Screwby turns up. The captain is an affable man and owes a long score at Curlington’s; but, as the head of that family represents to his wife, “belongs to such a slap-up lot,” that it would be suicidal to ask him for it; and besides, he brings so many clients – fresh and green and young – this Caspar of Pall-mall. Moreover, he has a friend around the corner who arranges little financial matters for Curlington’s hard-up customers, and in the question of commission is liberality itself. Mrs. Curlington does not altogether like him. She misdoubts his urbanity and marks the traces of late hours and strong waters in his bloodshot eye and luminous nose. Curlington is immensely relieved by his arrival, gives him “the office to get on” for him, while the eye of the missis is gazing on a passing lordling, and is a happy man – at least, till the race is run and the numbers up, when he reflects, like a few more Ascot revellers, that he had better have kept his money in his pocket. The loss of a fleeting fiver, however, does not spoil Curlington’s appetite, and he falls upon chicken and lobster like a famished wolf. He is right; for, somehow, lobster always tastes particularly well at Ascot. Whether its colour, as suggesting the livery of royalty, gives it additional zest, I know not; but it never has the same flavour anywhere else.

Outside the grand stand, still farther down the New Mile, are thousands of spectators enjoying the heat and throng, the dust and din of racing-time. There is vast eating and drinking, and the professors of the time-honoured three-card trick are dodging the police and making hay while the sun shines. Just before the last race, there is a move towards the railway station – the three-card men making their appearance again – the drags move off, and the merry company begins to melt away. The excitement of the day is coming to an end, and the racegoers disperse, some heading back to London, some to nearby towns and villages, and some staying in the charming cottages that line the New Mile.

For many, the day has been a mixture of joy and disappointment, with some reveling in their successful bets and others lamenting their losses. The atmosphere is still lively, but the anticipation of the next day’s races is already building. Those who have made Ascot their temporary home for the week are looking forward to more days of thrilling horse racing, socializing, and indulging in the pleasures of the turf.

As the sun begins to set, the heath returns to its peaceful state, and the echoes of the day’s excitement fade away. Ascot, with its storied history and timeless traditions, remains a place where horse racing enthusiasts, fashionistas, and socialites come together for a week of merriment and enjoyment, creating memories that will last a lifetime. And so, until the next day dawns, the spirit of Ascot lingers, ready to rise again with the sun and continue its age-old celebration of sport and society.

Not, however, the happy dwellers on the line of the New Mile. These retire to their quiet cottages, and, mingling the perfume of their cabanas with that of the rose and honeysuckle, talk over the weights and chances of the next day. As the evening settles in, the atmosphere is filled with a sense of anticipation and camaraderie. Friends and neighbors gather in their cozy abodes, savoring the tranquility after a day of excitement.

In these charming cottages, surrounded by the natural beauty of Ascot, conversations revolve around the equestrian world, the prowess of the jockeys, and the promise of new races. Bet strategies are devised, and tips are shared with a mix of expertise and friendly banter. The joy of being part of the racing community and the excitement of the coming days fill the air.

As the sun dips below the horizon, the lights from the cottages start to twinkle like stars, casting a warm glow on the New Mile. Inside, laughter and camaraderie continue late into the night. The spirits are high, and the love for horse racing and the traditions of Ascot bring everyone together.

In these moments, as friends and family share their passion for the sport, the magic of Ascot is felt not only in the grandstands but also in the intimate gatherings of those who call this place home during the racing week. The cottages along the New Mile become sanctuaries of joy and camaraderie, where the spirit of Ascot is cherished and celebrated in its purest form.

And so, as the night deepens and the stars shimmer above, the residents of the New Mile retire to their beds, eagerly awaiting the dawn of another day at Ascot. A new chapter of excitement, camaraderie, and the timeless allure of horse racing awaits, and the spirit of Ascot lives on, forever ingrained in the hearts of those who have experienced its magic.

More about Berkshire

- Old Images of Berkshire, EnglandGlimpse history through old images of Berkshire, England.

- Old Images of Ascot, BerkshireGlimpse history through old images of Ascot, Berkshire, England.

- Old Images of Ascot Racecourse, BerkshireGlimpse history through old images of Ascot Racecourse, Berkshire, England. Improvements 1934 An “All Weather” Ascot (1934) – British Pathé on YouTube Royals 1934 Mayfair Migrates (1934) – British Pathé on YouTube Runners 1938 Cross Country Race On Ascot Course Lner (1938) – British Pathé on YouTube Horse Races 1951 Ascot festival horse races (1951)… Read more: Old Images of Ascot Racecourse, Berkshire

- Old Images of Eton College, BerkshireGlimpse history through old images of Eton College, Berkshire, England.

- Old Images of Hungerford, BerkshireGlimpse history through old images of Hungerford, Berkshire, England.

- Old Images of Thatcham, BerkshireGlimpse history through old images of Thatcham, Berkshire, England.

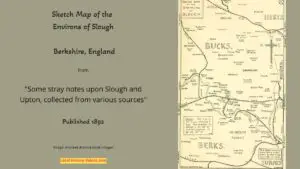

- Old Images of Slough, BerkshireGlimpse history through old images of Slough, Berkshire, England.

- Old Images of Reading, BerkshireGlimpse history through old images of Reading, Berkshire, England.

- Old Images of Windsor, BerkshireGlimpse history through old images of Windsor, Berkshire, England.

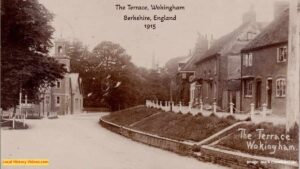

- Old Images of Wokingham, BerkshireGlimpse history through old images of Wokingham, Berkshire, England.