Glimpse history through old images of Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, England.

Old Photos of Wisbech

Fruit Pickers (1963)

Even as late as the 1960s, groups of family and friends, including small children, would leave the East End of London for fruit picking jobs in the British countryside.

They were paid according to the weight of the fruit they picked, and had basic accommodation provided in farm site chalets.

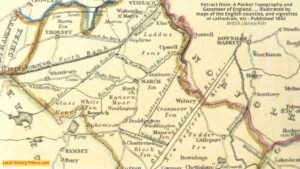

The newreel here shows a large group travelling by train to Wisbech East, then in Norfolk.

Fruit Special (1963) – British Pathé on YouTube

A bit of Wisbech history

Extract from:

“The History of Wisbech, and the Fens“

by Neil Walker and Thomas Craddock

Published in 1849

Pages 490 – 494

The utility of marts and fairs is now almost wholly superseded; and those of Lynn and Wisbech have degenerated into a mere gathering of freaks of nature, “harlotry players,” dirty exhibitions, conjurors, wild beasts, and ragamuffin life in all its gipseyism.

When there were few or no shops, and private families as well as religious fraternities resorted to annual fairs for their annual necessities, fairs were important features in the national system.

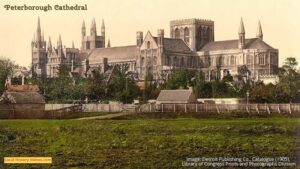

In such ages, the great fairs of Stirbridge and Peterborough had their origin; but Lynn and Wisbech Marts came in a more degenerate age, and though they were formerly, especially Lynn, extensively resorted to for business, they seem never to have attained the commercial importance that Peterborough manifests even at the present day.

When its period is short, however, Wisbech Mart still presents an active scene; but it is doubtful whether the rapid change which society seems now undergoing may not, in a few years, sweep it out of existence.

All institutions of a purely fanciful or holiday character are looked upon as thriftless idleness by an age that values itself on lengthening, not abridging time, and giving to minutes the value of hours. Amusement gains little mercy from so industrious a generation.

There are, however, other fairs attached to Wisbech, which, although coming within the description of business fairs, cannot boast the popularity of the Mart.

There are two fairs for horses and one for bullocks. The former have degenerated within the memory of the living, but the last-named has maintained its character with sufficient regularity. It is held in the streets and is sometimes the means of a considerable change of stock.

On consulting Gazetteers and Almanacks, we are enlightened with three other fairs attached to Wisbech – for Hemp and Flax, on the Saturday before Palm Sunday, the Saturday before Whit Sunday, and August 1st; but the celebration of these is almost if not wholly confined to the pages which announce them.

They are unknown to the majority of the inhabitants; a generation is gone since any transactions in an amount worthy the name of a fair was made in Wisbech.

Formerly, when these articles were largely grown in the neighborhood, they used to constitute commodities of considerable traffic, but the traveler may ride over the whole Fen without now finding an acre of either – commodities of a richer and more lucrative description having superseded these vegetables of a colder and more impoverished character.

Allied to fairs, and in some sort partaking of the nature of a pleasure fair, is the Statute, held annually a week or two before Michaelmas. It is a custom purely attached to the agricultural districts, and is still sustained here with a spirit beyond the generality of institutions of so primitive a character.

One of the peculiarities of the times is the prevalence of Literary and Scientific Societies; but in proportion as the age has advanced such societies from cities to towns, and from towns to hamlets and villages, Wisbech seems to have gone back, or only to have made abortive efforts at their establishment.

One Literary Society has indeed existed since 1781, and has now accumulated a library of several thousand volumes. But although the population of the town has doubled – intelligence according to the hackneyed vanity of the age trebled – every attempt to establish another on a more liberal principle has failed.

Every member on admission into this Society pays £2 2s., and an annual subscription of £1 1s., and they have recently by a compact with the proprietors or Trustees of the Museum procured a large room as a Library in that building.

The books being of that miscellaneous description which pleases general readers cannot be expected to be very select, though by an almost universal renunciation of novels and romances, works of a more permanent character than would otherwise have been received have accumulated.

We have a more unsatisfactory record to make of Mechanics’ Institutes or Scientific Societies. At the latter end of the last century, a Society supported by a few inquirers flourished for twenty-five years and died at the very era when Scientific Societies were growing into a rage.

Three other Societies based on principles of Science – the Scientific Society in 1834, the Mechanics’ Institute in 1836, and the Wisbech Institution in 1837 – have all been overcome by want of patronage in the same cause.

We do not know that Wisbech has acted in any way absurd in this.

The idea of Science for the people is one of those airy dreams so common to the age, and so unsubstantial. Science is not for the people, and it may be doubted whether Wisbech, with no Scientific Society, is not as far advanced in Astronomy, Chemistry, and Natural Philosophy as other towns which have had all the advantage of profound lectures and well-supported establishments.

Science is no more to be learned in the lecture-room or by mere societies than farming or cabinet-making. Science only differs from the common working crafts in that it requires as much hand labor and an infinitely greater labor of the brain. A chemist must work like a blacksmith, a geologist like a stone-breaker, an anatomist like a butcher.

Scientific Societies may popularize a science, as they have done geology and chemistry, by exhibiting the fiction-like facts of the one and the necromantic brilliancies of the other; but these are only sports or lures; and he who expects a science to be composed of such materials would believe with as much rationality the narratives of the old travelers, who represented their countries as glittering with diamonds and gold.

The last-named society, the Wisbech Institution, expired in 1845, after having lived eight years. It was established under good auspices – town and country hasted to become members, and for a time, it bore the appearance of prosperity. But after flourishing for four years and languishing for four years, its property was sold by auction, and no other institution of the character seems likely to take its place.

Were Englishmen of a less political character, there would be more chance for its Literary and Scientific Societies. But the intervals of business are so well filled with political study that the higher arts have little chance and are abandoned to their professors or a minor portion of society.

Bonaparte called England a country of shopkeepers – he would scarcely have been in error if he had called it a country of statesmen. It is not, therefore, surprising that among all the rise and fall of Literary and Scientific Societies, a news-room should have flourished in unabated vigor, and still continues to exist with even renewed life.

Other societies, such as the Humane Society for restoring persons near drowning, the Dorcas Society for providing clothing to the poor, and the Female Friendly Society with the same philanthropic purpose, give a creditable coloring to the humanity of the town and are supported with spirit.

General Cemetery.

In an enumeration of the public objects of Wisbech worthy of visit and description, the General Cemetery must not be passed over.

For many years prior to its establishment, the Churchyard, the sole public burial place, had become so crowded and even infectious that it was the shame of the town, and an object of disgust rather than veneration, even to those whose generations had been interred there.

Animated by these considerations, a company of gentlemen endeavored in 1836 to purchase a piece of ground by the establishment of a company of shareholders, each contributing £5. After a little time, a very appropriate piece of land consisting of 3 acres, 2 roods, 3 perches, was purchased for £950, subject to an annuity of £17 during the life of the original proprietor. 210 shares of £5 each, held by 85 shareholders, were quickly obtained for the purchase, and immediate steps were taken for making the ground ornamental and fitting it for interments.

It is situated on the west side of the river near the Leverington Toll Bar. In 1840, it was vested in the hands of 21 Trustees and enrolled in the High Court of Chancery.

The principle of its establishment is the most liberal. Churchman or Dissenter of any sect may be interred according to his own peculiar ceremonies without any restraint or interference.

After the purchase had been completed, which was an extremely favorable one, the Committee of Management set about laying out the ground in an ornamental manner, planting evergreens and other shrubs and trees, and, in short, making the place more like a pleasure garden than a receptacle for death.

The example of Père Lachaise, in Paris, and of Kensal Green and Highgate Cemetery in London, had perhaps incited this ambitious feeling; but whatever it might be, the public has received an essential benefit in an almost public garden, where the beauties of vegetation, arranged and cultivated by art, may be enjoyed.