Glimpse history through old images of Wells, a Cathedral city in the Mendip district of Somerset, England.

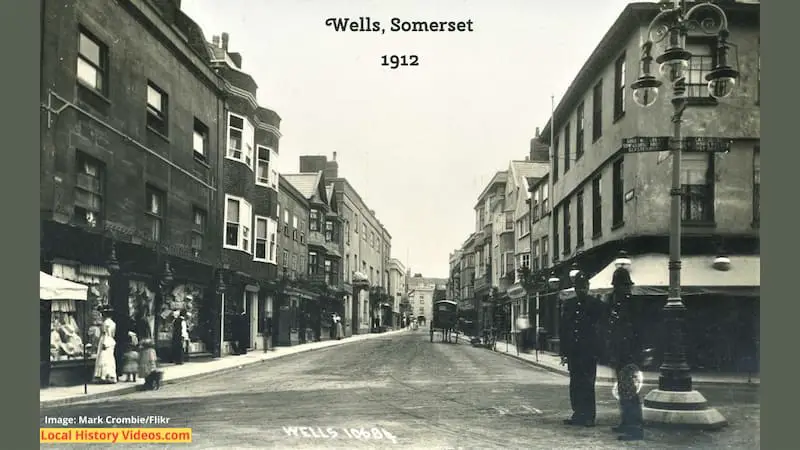

Old Postcard of Wells

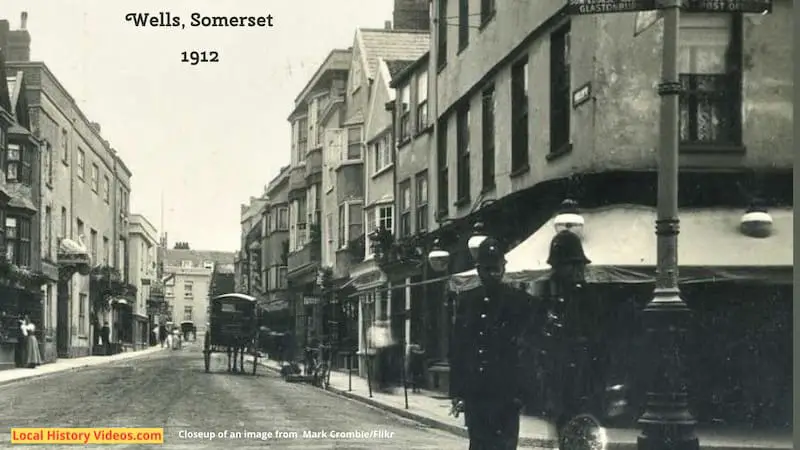

The image above is an old postcard sent in 1912. The view is from the junction at Market Place, looking up Sadler Street.

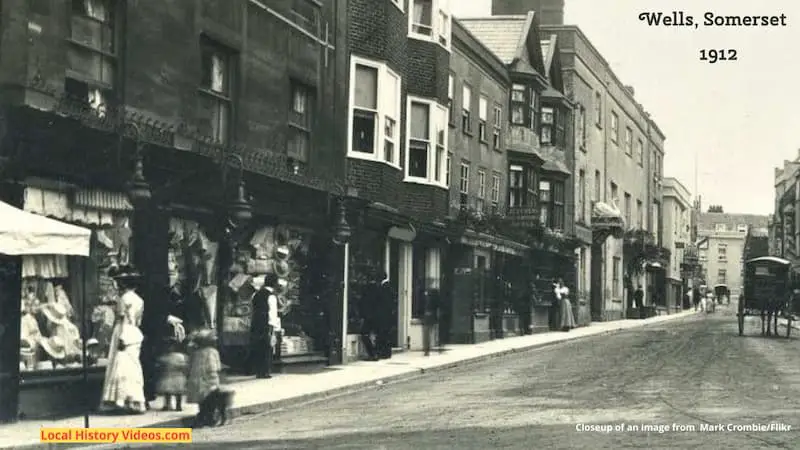

I’ve added a couple of closeups here so you can see more detail. Just click on them and they should open to a full screen.

Wells Cathedral in 1939

This newsreel from 1939 introduces us to the 12th century Wells Cathedral, with its never finished two western towers.

We look down to see the 13th century Bishop’s Palace, built by Bishop Jocelin, thought to be the only medieval dwelling house in Britain still intact within its own fortifications, moat, and drawbridge. Jocelin of Wells died on the 19th November 1242, but his arms remain in place on the largely intact ancient property.

In the 1870s, the daughter of John Hervey, then the Bishop of Bath and Wells, trained swans to ring a bell in the moat’s gatehouse when they wanted to be fed. We see here the swans still following the tradition in 1939.

In October 2018 the bell-ringing swan Bryn died, and his partner and cygnets relocated to another swan community. So in May 2019 the charity Swan Rescue South Wales relocated a breeding pair of swans from their unsuitable environment in Droitwich into the moat, ready to teach them how to ring the bell.

Wells Cathedral Etc. (1939) – British Pathé on YouTube

Historic Book

Extracts from “The Somerset Diocese, Bath and Wells”, by William Hunt.

Published 1885

Page 5

“What is really important is that “the old church” of wicker and timber, the object of the veneration of Briton, Englishman, Dane, and Norman, enriched alike by Ini and by Cnut, lived on through successive shocks of conquest; and still, in another shape, as the ruined church of St. Joseph, bears witness that, in the larger part of the diocese of Bath and Wells, the worship of Christ was never displaced by the worship of Woden.”

Page 15-17

“During the troubles of the Danish wars no measure of ecclesiastical reform could be taken in hand. And when the western land had rest under Eadward, the son of Alfred, several dioceses appear to have been vacant. Eadward and Archbishop Plegmund held a council in 909 to remedy this state of things.

The West Saxon land was redivided, and Somerset received a bishop of its own. His see was planted at Wells. At first sight the choice may seem strange, for Wells is, and ever has been, a small place. An English bishop, however, unlike the bishops of the continent, was the bishop of a people rather than of a city. The early English system of administration was local rather than central, and was carried on through popular rather than royal institutions. There was, then, nothing really strange in the choice of Wells, for it was fairly convenient for the work of a bishop who had the spiritual supervision of the Sumorsætan.

There must, however, have been some special reason for the choice, and this reason seems to have been that an ecclesiastical establishment of some size already existed there. Tradition declares Ini to have been a founder at Wells, and some truth generally underlies even a false tradition. Besides this, a charter of Cynewulf, dated 766, records a grant “to the minster near the great spring at Wells for the better service of God in the church of St. Andrew.” The charter may be spurious, and yet, like the tradition about Ini, may contain some truth. Eadward probably fixed the new see at Wells because there was a large church there, served by secular priests, and founded, it may be, by Ini. These secular priests would form the chapter of the new bishop, and, because his see (seat = cathedra) was placed in their church, it became the cathedral church of the diocese.

The first bishop of Wells was ATHELM, or Ethelhelm. He was consecrated in 909. He is said to have been an uncle of Dunstan, and, if this was so, he was of noble family, and was perhaps connected with the royal house. Before he was made bishop he seems to have been a monk of Glastonbury. He probably ruled well in Somerset, for in 914 he was made archbishop of Canterbury.”

Pages 22-26

“With his successor, DUDUC (1033-1060), we again begin to know something certainly, for Gisa, who followed him at Wells, speaks of him in a short account he wrote of his own life, which has been preserved in a treatise of the twelfth century on the early bishopric of Somerset.

Duduc was a native of the old Saxon land beyond the sea. The relations of Cnut with the Frankish emperor probably caused him to be brought into the king’s household as one of his chaplains. Before he was made bishop, he received from Cnut the abbey of Gloucester, and the estates of Congresbury and Banwell, which Alfred had given long before to Asser, bishop of Sherborne. According to Gisa,

Duduc, with King Eadward’s consent, left Congresbury and Banwell to the Church of Wells; and, when on his deathbed, further bequeathed to it his store of vestments, books, and the like. On his death, however, Earl Harold laid hands on the Somerset estates and on all the bishop’s movables.

The successor of Duduc was GISA (1061-1088), a Lotharingian and one of King Eadward’s chaplains. He gives a sad account of the condition of his see at his consecration. The church was small; the canons lived among other people, like parish priests; they were poor, and even, he says, forced to beg. Their poverty, however, could not have been the result of the loss of Duduc’s property, for the Church had never possessed it.

Gisa at once set about remedying this state of affairs. He obtained Wedmore from the king, and Mark and Mudgeley from the queen. He excommunicated a certain Elfsige, who refused to restore Winsham, and at last obtained that estate from William the Conqueror.

Harold, he says, he threatened with a like sentence; and when the earl came to the throne he promised to restore what he had taken away, and to give more besides, but, the bishop adds, divine vengeance overtook him.

The story of Gisa and Harold has been magnified, until the earl has been represented as reducing the Church of Wells to beggary. None of the possessions of the church were touched by Harold; the whole question concerns the right to the bequests of Duduc. If the earl had reason to believe that the bishop left his goods to the Church, he should not have interfered with the bequest. If not, then he had a right to take them as the movables of a deceased clerk.

As regards the estates, the right of Duduc to leave them depended on the terms of the grant. Gisa based his claim on certain charters of Eadward. If these charters enabled Duduc to alienate the lands, Gisa would, one would have thought, have sued the earl for them, and produced the deeds in the shire-moot. He pursued this course in the case of Elfsige, and only excommunicated him when he refused to give up Winsham, after the shire had declared the bishop’s right to it. With Harold, on his own showing, he trusted to threats and persuasion. And it is evident that he made no attempt to establish a legal claim in the next reign. From the Conqueror, indeed, he received Banwell, but Congresbury was not given to the Church until King John’s reign; and this partial compliance with Gisa’s wishes shows that it was a matter of favour and not of right.

In short, it is evident that Harold did not take away from the Church of Wells anything it ever had before, and it cannot be proved, to say the least, that he acted unlawfully in preventing it from acquiring Duduc’s bequests.

A charter, granted by Harold on coming to the throne, confirms Gisa in his possessions, and orders the king’s reeves in Somerset to help him to uphold the rights of his Church. This charter does not, of course, apply to the estates in question: it was probably granted because Harold felt the need of friends. Gisa acquired other lands besides those already mentioned, and among them the important estate of Combe. Some losses indeed he had, though, on the whole, the property he gained for the Church was considerable.

Both from his own record of these transactions and from the Domesday Survey, it is evident that the chapter had as yet no property of its own, apart from the bishop. The canons were dependent on him, and the two estates they had which were separate from his demesne were held of him as over-lord.

Gisa would not allow the canons to live any longer in their own houses, like parish priests, a custom which often led them to marry, and so to engage in secular work, and, according to his account, even to beg. He built a cloister, refectory, and dormitory; and made them eat and dwell together, binding them by the rule observed by canons in his own land, the rule of Chrodegang of Metz, which compelled them to live rather as monks than as secular clergy. The same course was pursued at Exeter by Bishop Leofric, who had been brought up in Lorraine.

Following out the Lotharingian system, Gisa caused the canons to choose an officer, called a provost, to look after their temporal matters. They chose a certain Isaac of Wells. The appointment of this officer was a step towards the separation of the property of the canons from that of the bishop.

It was quite against English ideas that canons should be made to live together in the monastic fashion insisted on by Gisa, and his reforms were doubtless disliked by the chapter. His work in this direction was undone by his successor.”

Page 107-108

“Finding that the chantry priests of Wells often fell into mischief, Bishop Erghum (1388-1400) founded a college for them, that they might dwell together, separate from the laity, and under fitting discipline. His foundation perished in the general ruin of the sixteenth century. Its memory is still preserved in the name of College Lane.”

Page 198-199

“Bulls were baited within the cathedral precinct, and the sport was enforced by law, for it was considered that it made the flesh more wholesome. Accordingly we find that in 1612, a Wells butcher was summoned before the city-magistrates for having slaughtered a bull “not first bayted.”