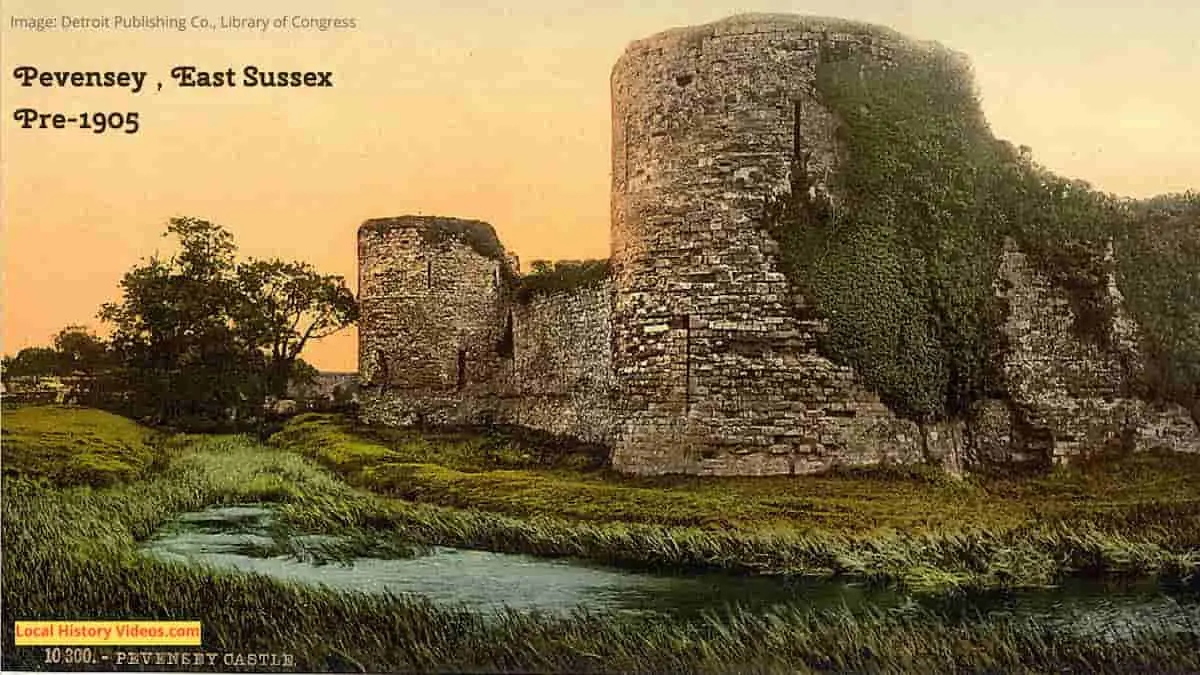

Glimpse history through old images of Pevensey, East Sussex, England.

WWI V.A.D.s at Pevensey

The Voluntary Aided Detachments, or VADS as they were commonly known, were civilian volunteers who provided nursing care for wounded soldiers recouperating in the UK, drove ambulances in France, and supported refugees in Egypt.

The unit was created after the Boer War, but grew quickly to 40,000 members at the start of the Great War, later known as World War I.

The V.A.D.’s Smart Ambulance Practice At Pevensey Bay (1914-1918)- British Pathé on YouTube

The Vads Smart Ambulance Practice (1914-1918) – British Pathé on YouTube

Pevensey Castle in the 1970s

First is some footage recorded in 1974. It starts with aerial views, then views the castle within its landscape, before moving in to the interior of the castle ruins.

Pevensey Castle | East Sussex | A place in history | 1974 – ThamesTv on YouTube

Next, in undated footage from the 1970s, we see a few moments of Pevensey Castle, before the scenes move on to Hastings and then Dover.

Pevensey and Dover Castle (1970-1979) – British Pathé on YouTube

A Bit of Pevensey History

Extract from:

A Compendious History of Sussex, Topographical, Archæological & Anecdotical. Containing an Index to the First Twenty Volumes of the “Sussex Archæological Collections”

by Mark Antony Lower

Published in 1870

Pages 89-92

PEVENSEY .

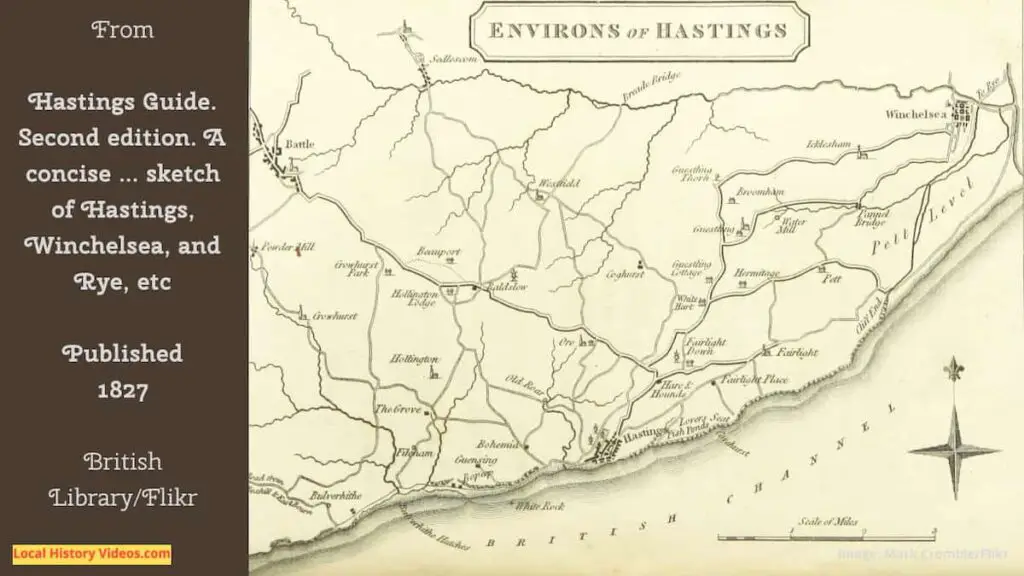

Domesday, Pevenesel; vulgo, Pemsey; a parish and Railway station (though the latter is locally in the parish of Westham) in the Hundred and Rape of its own name; distant ten miles west from Hastings. Union and Post-town, Eastbourne. Population in 1811, 254; in 1861, 385.

Benefice, a Vicarage, valued at £1,100; Patron, the Bishop of Chichester; Incumbent, Rev. Henry Browne, M.A., of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. Date of earliest Parish Register, 1566. Acreage, 4,856.

No place of the same small population and minor importance in the South of England can vie in interest with Pevensey.

Though now only a simple village street, it represents a great Roman station and fortress, and a very considerable stronghold of medieval days; and was the scene of many exciting historical events extending over centuries.

It gives name to a hundred, a rape, a rich marsh, and that beautiful expanse of ocean, Pevensey Bay.

It also possesses a separate jurisdiction, the “Lowey” or liberty, comprising the parishes of Pevensey and Westham, with portions of Hailsham and Bexhill, and is one of the principal limbs or members of the Cinque Ports.

The great and fertile plain stretching along the Sussex coast from the eastward of Beachy Head in the direction of Hastings, and inland towards Wartling, Hurst-Monceux, and Hailsham, now studded with great and fat beeves, was at some remote era covered by the sea, and what are known as “eyes” or elevations above the surrounding level – such as Chilleye, Northeye, Horseye, Rickney, &c., must have been islands, forming a miniature archipelago.

As these are all of Saxon meaning, it may be presumed that, at the time of Saxon colonization, they were frequently or constantly insulated.

It is almost certain that within the last thousand years, the waters approached very closely the town and castle of Pevensey, and even so lately as the year 1317, Edward II. granted to one Robert de Sassy, by the annual service of presenting a pair of gilt spurs, certain lands in the marsh of Pevensey and in the tenure of no man, because overflowed by the sea.

Like Hastings, Winchelsea, and Seaford, this place has, by the caprices of Father Neptune, lost the port which it once enjoyed, and it now requires almost a stretch of the imagination to believe that royal navies once rode in Pevensey harbour.

Such, however, we have evidence in many ancient records was once the case.

What gave importance to the place in the days of the Roman rule in Britain was the erection of a large fortification or castrum, which has been undeniably proved to be the station called ANDERIDA, a word latinized from the British name Andrads wald.

The Britons appear to have had a settlement here in earlier times, both from the occasional discovery of British coins, and from the retention of Celtic words as names of places.

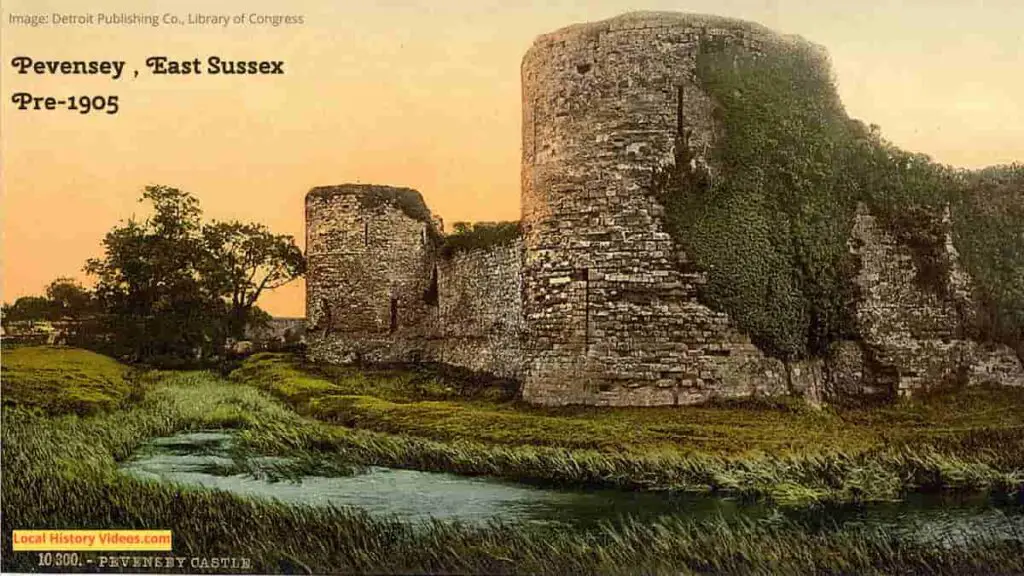

The Castle of Pevensey, as we now behold it, exhibits two periods; the one undoubtedly Roman, the other a medieval building, engrafted upon the original structure.

The date of the Roman building is inferred to have been of about the commencement of the Lower Empire.

In the excavations which, in connection with Mr. C. Roach Smith, F.S.A., I carried on on the spot, we found coins of Gallienus, Postumus, Maximinian, Constantine, the Constantine family, and Magnentius. Other coins of corresponding dates had been previously found on the spot, and they still frequently turn up.

It was long a matter of archæological discussion whether Pevensey was the true site of Anderida.

Seven other places have set up their claims to the honour, but the names of Petrie, Arthur Hussey, Roach Smith, and Thomas Wright are arrayed on this side.

The arguments are too lengthened for even a précis here; nor is it necessary, as the site is now fixed here by common consent.

After the withdrawal of the Romans from Britain, some of the native Britons took up their residence in and around this stronghold, from which they were expelled by Ella, the Saxon invader, and first king of the South Saxons.

After the utter subjugation of the former, the Saxons gave to this place the name of Andredes-ceaster.

The siege and subsequent slaughter of the poor inhabitants are described by ancient chroniclers as dreadful in the extreme.

It is not until the year 792 that Pevensey appears under its modern appellation. It was then given, together with Hastings and Rotherfield, by the Saxon Duke Bertwald, to the abbey of St. Denis near Paris, in return for a miraculous cure wrought on him by the bones of St. Denis himself, and those of others in that holy place.

Here occurs another hiatus until A.D. 1042, but from that date a pretty connected history of Pevensey exists.

In that year, Swane, Earl of Oxford, a son of Godwin, Earl of Kent, who had been compelled to fly into Denmark for attempting an illegal marriage with Edgiva, Abbess of Leominster, returning to England with eight ships, landed at the port of Pevensey.

In 1049, Earl Godwin and his son entered the port and took away many ships.

The crowning event in the history of Pevensey was the landing there of William, Duke of Normandy, 28th September, 1066, a few days previously to his victory over Harold at the Battle of Hastings.

The particulars of the chain of events connected with the Norman Conquest belong rather to general than local history; but several papers and notes in “Sussex Archaeological Collections” serve for illustration.

The celebrated piece of needlework, known as the Bayeux Tapestry, contains a representation of the landing AD PEVENESAE, the drawing up of the ships, the disembarkation of the horses and men, and several horsemen galloping towards Hastings in search of food for the army.

On the partition of the conquered lands, William bestowed the Rape of Pevensey (more than a sixth part of the county of Sussex) on his half-brother, Robert, Earl of Mortaigne, or Moreton, besides many others in other counties, amounting altogether to nearly 800 manors, of which 54 were in Sussex.

He doubtless restored the outer walls of the Roman Castle, long a partial ruin, and added the little, or medieval castle, within the enceinte of the older fortification, making it at the same time the caput baronie of his Sussex estate.

In 1067 William returned to Normandy to receive the congratulations of his ancient subjects, taking with him as hostages Edgar Atheling, Archbishop Stigand, and others.

He determined to sail from the same port at which he had landed, and accordingly embarked from Pevensey in the spring of the year.

Domesday contains a detailed account of Pevensey in 1086. It was in the territory of the Earl of Mortaigne. In the reign of the Confessor, that king held 24 burgesses in domain, the toll producing 20s., port-dues 35s., and the pasturage 7s. 3d. rent. The Bishop of Chichester had five burgesses, and three priests had amongst them 23 – a total of burgesses in domain 52.

At the time of the Earl’s succession to the manor, there were but 27, but twenty years later, at the making of the Record, the number arose to 109, and the toll produced £4. Thus it would appear that the Normans improved the condition of Pevensey in the early days of their rule. The town had a mint, which is mentioned.

In the remarkable discovery of 26,500 coins at Beaulieu, Hants, some years since, there were some struck at this place, with the name of the moneyer – JELFHEN – PEFNS.

More about East Sussex

- Old Images of Wannock, East Sussex

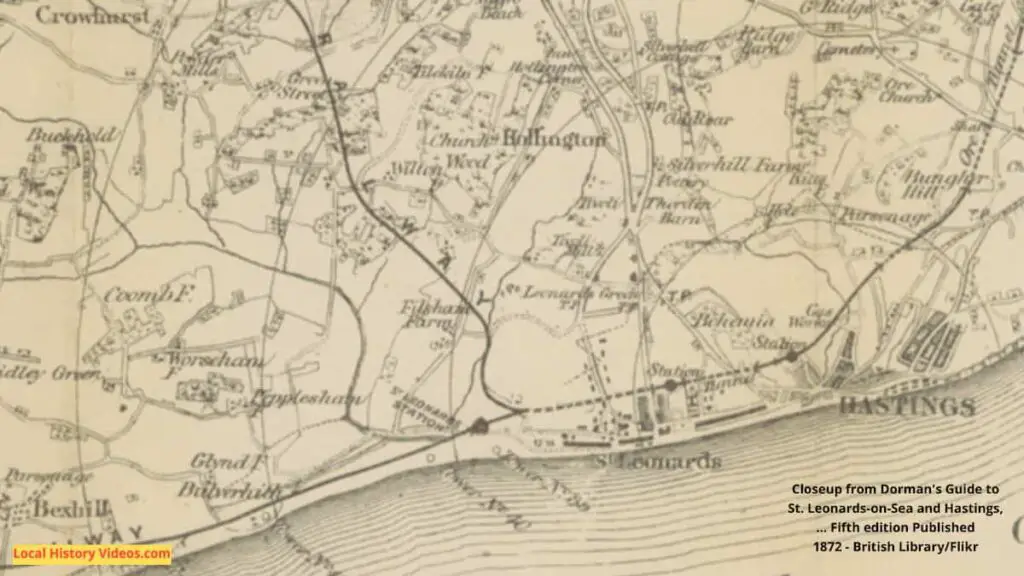

- Old Images of St Leonards-on-Sea, East Sussex

- Old Images of Crowhurst, East Sussex

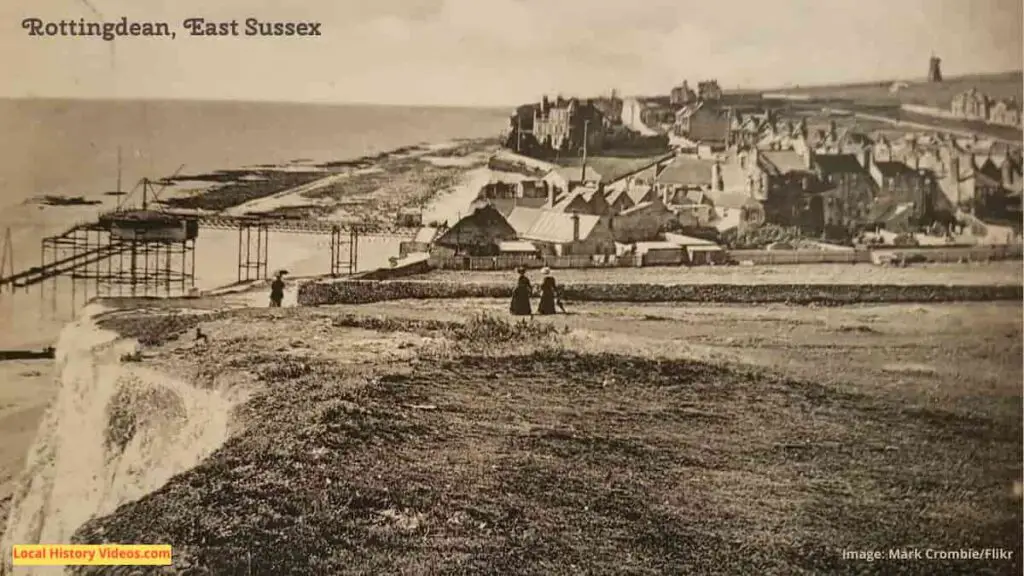

- Old Images of Rottingdean, East Sussex

- Old Images of Pevensey, East Sussex

- Old Images of Hailsham, East Sussex

- Old Images of East Sussex, England

- Old Images of Winchelsea, East Sussex

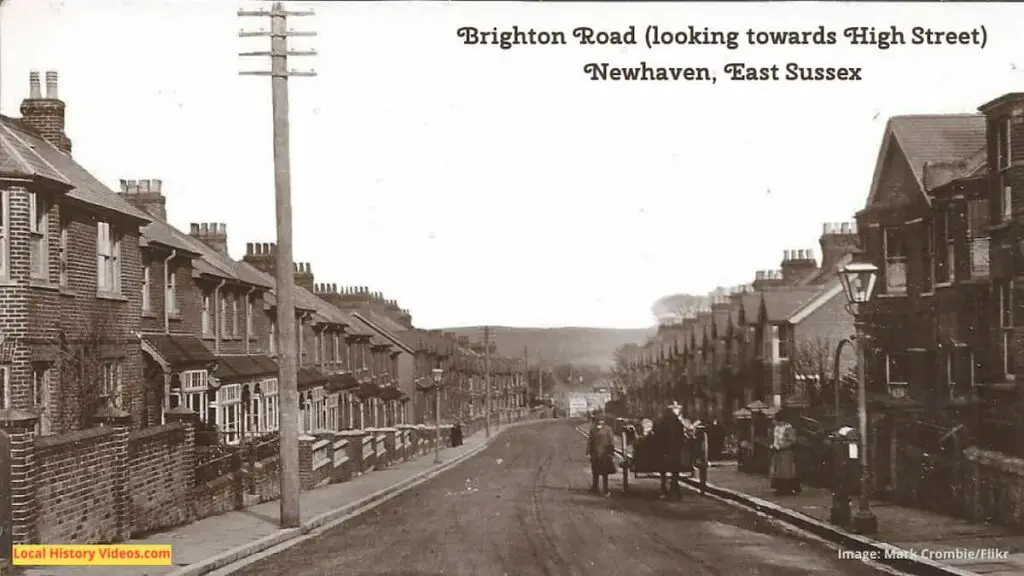

- Old Images of Newhaven, East Sussex

- Old Images of Lewes, East Sussex